A blustery autumn afternoon in Dublin. Sudden clouds have cooled the red rays of a setting sun, and the resulting grays cast soft shadows on the faces of students lazily thumbing their smartphones in the lobby of the library at St. Patrick’s College Drumcondra. Behind them more than a dozen children, teachers, and administrators sit quietly. They’re awaiting the arrival of Satya Nadella, chief executive of Microsoft , the Seattle-area technology titan that was once the largest and most powerful company on the planet.

Glass doors swing open and in strides Nadella, a clutch of senior staffers in his wake. He makes a beeline toward the waiting schoolchildren, pumping the hands of several administrators along the way. He sits and asks four students, each about 10 or 11 years old, what they have been working on. A boy with Robert Plant locks indulges, gesturing to a tablet computer as he haltingly explains the three-dimensional world he has coded in the game Minecraft—Nadella’s first major acquisition as Microsoft’s CEO. Nadella responds with a huge grin. “Amazing,” he says. “I need one of those.”

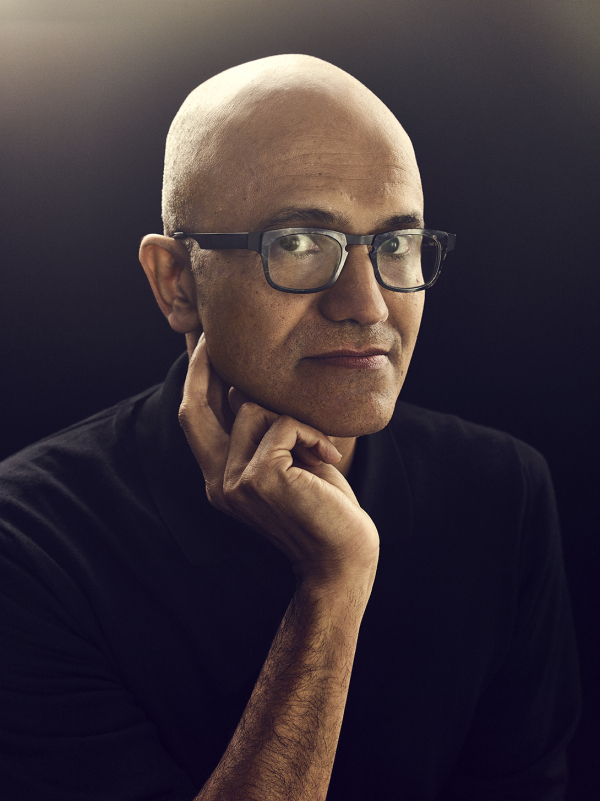

And then Nadella is on his feet again. He’s six feet tall, but he’s got the lean physique of a long-distance athlete and a shaved head, both of which accentuate his taut silhouette, making him seem taller. Nadella runs 30 minutes each morning, preferring the treadmill to spare his 49-year-old knees from the ravages of concrete. He is deeply protective of this time; it’s one of the few moments in his highly orchestrated day when he’s alone with his thoughts.

But Nadella consistently reserves time for sessions with children—partly because they are the next generation of customers, and partly because it keeps him grounded. Nadella moves to another group of kids and then shifts his attention to a teenage student who is blind. The young woman has been working on building accessibility features using Cortana, Microsoft’s speech-activated digital assistant. She smiles and recites the menu options: “Hey Cortana. My essentials.” Despite his transatlantic jet lag Nadella is transfixed. “That’s awesome,” he says. “It’s fantastic to see you pushing the boundaries of what can be done.” He thanks her and turns toward the next group.

“I have a particular passion around accessibility, and this is something I spend quite a bit of cycles on,” Nadella tells me later. He has two daughters and a son; the son has special needs. “What she was showing me is essentially how she’s building out as a developer the tools that she can use in her everyday life to be productive. One thing is certain in life: All of us will need accessibility tools at some point.” All the better if Microsoft can provide them.

And then Nadella is gone. The executive spent just a few minutes with each group of children, tearing through the room like a tempest. By the time the twentysomething students milling around St. Patrick’s realize that an important person has descended upon their campus, he has disappeared—on to the next room, the next city, the next country in a whirlwind four-day tour that will take him to the European continent and through some of his company’s largest markets.

When Nadella replaced Steven Ballmer as Microsoft’s CEO in February 2014, he inherited what you might diplomatically call a growth crisis. Undiplomatically, you might call it an existential one. “Microsoft is unable to connect with the new generation of users,” wrote Global Equities analyst Trip Chowdhry in a 2010 research note to his clients, about as damning a sentence as you can muster for a technology company.

Microsoft, the behemoth of Windows and Office, was fast approaching its 40th anniversary. It had the kind of cash reserves that military dictators kill for and the market share of business-school dreams. But none of the new products the company had produced under its second CEO—from its Bing search engine to its Zune, Kin, and Lumia mobile devices—generated anywhere near the revenues of the smash hits created under its first, cofounder Bill Gates.

Microsoft entered the twilight of Ballmer’s tenure as the most successful and wealthiest desktop-software company the world had ever seen—at a time when the world had moved on to search engines, social networking, mobile devices, and cloud computing. For the first decade of the 21st century, Microsoft was the world’s most valuable company, topping out at more than $600 billion. Apple AAPL -0.60% ended that run in 2010, riding its legendary turnaround under CEO Steve Jobs. By this point, for the first time in its history Microsoft was facing the prospect of a decline in its core business.

Since Nadella took charge, the company has been engineering a stunning turnaround of its own. He has taken a company focused on personal computing but showing promise in its enterprise and cloud-computing businesses, and turned that equation on its head. In the past three years Microsoft sheared the $9.4 billion phone business it acquired from Nokia and sold its Bing mapping-data assets to Uber. It plowed billions into the construction of data centers around the globe to support its now cloud-ready products. And it made substantial leaps transforming its original software business from permanent licenses, where revenue is a one-time affair, to subscriptions, where revenue is recurring.

Nadella has even struck an audacious deal, plunking down $26.2 billion for business-networking company LinkedIn, the largest acquisition in Microsoft’s history. That’s a massive check to write, and “largest acquisition in Microsoft’s history” is a dubious title given the company’s, um, checkered track record in that realm. Optimism, it’s fair to say, has returned to Redmond. “Satya is a great leader for Microsoft,” says Ballmer, who is still the company’s largest individual shareholder. He adds that Nadella “has done a great job improving perceptions of the company in ways that can advance its agenda— with developers, industry participants, and investors.”

As rival Apple—with a market capitalization of $600 billion, still the world’s most valuable company—weathers criticism of ennui under CEO Tim Cook, Microsoft has sharpened its focus under Nadella. In October the company’s shares surged past their all-time high price of $59.56, recorded in the heady days of the dotcom bubble and at the tail end of a decade that the company unquestionably ruled. Never mind that because of aggressive stock buybacks that reduced the company’s share count, Microsoft’s market cap is $460 billion, far below the old peak.

Still, the share-price resurgence was no small matter. For more than a decade Microsoft was a dead stock walking. Seemingly overnight the company was back with a vengeance. At its helm is a skinny, contemplative student of the world who revels in asking questions and couldn’t be bothered by so trivial a pursuit as warring with the company’s rivals.

The Palais Des Congrès, a hulking and angular 1970s-era convention center in the 17th arrondissement of Paris, was constructed on the former site of Luna Park, the largest amusement park ever built in the French capital. In the early 1900s the site was a monument to leisure. Today it is a temple to trade, with more than 344,000 square feet of glossy exhibition space on eight floors.

On a sunny October day the Palais is humming with thousands of people who have come for Microsoft Experiences, the company’s annual customer conference in France. Brightly colored booths promoting mobility and collaboration technologies pack the exhibition area. Attendees scurry between technical talks on DevOps and brainstorms about digital banking.

Satya Nadella is No. 5 on our Business Person of the Year list.

Inside one session, the “Blockchain Hackademy,” Nadella stands at the center of a scrum of engineers. He inspects a display showing energy-monitoring software and peppers an executive with questions. Nearby, a man wearing a costume in the shape of a Tetris block dances and hands out brochures about supply chain traceability. In Dublin, Nadella met his future customers; in Paris he is scouting future technologies. “From Bill to Steve to me, the worldview we’ve had is ‘long-term relevance,’ ” he later tells me. “It’s the batting average. You may strike out sometimes, but you’ve got to be able to, in this tech business, catch enough of them to survive in the major leagues.”

Nadella is behind schedule today, owing to some extended meetings with government officials earlier in the morning. “I’ve oftentimes described the role that Satya is in as almost like a head of state,” says LinkedIn CEO Jeff Weiner, comparing him to the CEOs of Apple, Facebook, and Google “Tim Cook’s job, Mark’s job, Sundar’s job—it’s akin to that in terms of serving multiple constituencies.”

The CEO’s schedule stipulates that he’ll remain at the blockchain session for 30 minutes, but he disappears through a side door in only a handful. His usual half smile has given way to a grimmer expression, and he charges down the crowded hall with his staffers in tow. Nadella moves so quickly that I lose him in the throng. When I finally find him, he is seated behind an unmarked door, getting makeup for his keynote and reviewing points with Caitlin McCabe, his fastidious chief speechwriter.

Nadella’s address will begin the same way as all the others he delivers this week. He will first cite Microsoft’s mission to “empower every person and organization on the planet to achieve more” and acknowledge his own beginnings in India as a sign of the power of technology to democratize society. He will quickly move to painting a future of computing anchored in the so-called cloud. He will acknowledge the various forms this future takes—“small screens, large screens, in your living rooms and your conference rooms”—and echo the view that the world is facing a “fourth Industrial Revolution.” (After mechanical, electrical, and digital, it’s a blurring of the three through the cloud-powered Internet of things.) And since he is in Europe, where data privacy laws are notably stringent, he will punctuate each address with no fewer than three mentions of the word “trust.”

I will listen to Nadella give a version of this speech four times this week—in Dublin, Paris, Berlin, and London. The bulk of his preparation happens months before at Microsoft headquarters. There Nadella, McCabe, and company workshop ideas and test them out on a real audience. (“To get the brutal, honest feedback,” he says.) Onsite, the CEO reviews only localized elements meant to cater to his audience—a partnership with Allied Irish Bank in Dublin, a deal with Renault-Nissan in Paris.

As Nadella prepares for his keynote speech in France, his chief of staff, a towering Princeton man who could double as a chief of security, stands guard outside the door. Every three minutes a staffer checks on his progress. Eventually Nadella emerges, slightly more at ease. He overhears my voice and pauses to ask how I’m doing, having followed him across international borders twice in 48 hours in pursuit of this story, with two more countries to go. I ask him in kind. “Halfway, is it?” he says, referring to his week’s breakneck schedule. “Not even,” I reply. He smiles and chuckles at our mutual misfortune, then marches into battle.

In many ways, Nadella was an unusual choice to lead Microsoft in a moment that called for transformation. He is a 24-year veteran of the company. He is an electrical engineer, not a product visionary.

But closer scrutiny reveals a man who managed to thrive as an exception to a corporate culture built on type-A personalities—the very kind that his predecessor embodied. It is a skill that helped propel Nadella’s unlikely rise, says Blake Irving, who joined Microsoft the same year as Nadella and went on to work with him in the company’s cloud-computing division before becoming CEO of GoDaddy.

“There are two types of conversations you’d have at Microsoft when you’d explain things,” Irving says. “One type of person waited for a break in the argument to argue back. The other listened to learn. That was Satya.” Well before he was named CEO, Nadella “could suspend his disbelief and opinion to listen to you thoughtfully. The slight difference between listening to argue and listening to learn is not subtle. It’s huge. Satya is soft-spoken but energetic, which is a weird combination.”

Satya Nadella—officially Nadella Satyanarayana—was born in Hyderabad, India, in 1967. He is the only child of Bukkapuram Nadella Yugandher, an officer for the Indian Administrative Service, the country’s civil service agency, and the late Prabhavati Yugandhar, a professor of Sanskrit. He grew up at a time when communist guerrilla fighters called Naxalites clashed with the government of Indira Gandhi.

The civil unrest shaped Nadella’s view on how to mobilize change. “One afternoon I saw two photographs that haunt me still,” he recalled at a 2015 dinner held in honor of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. “I saw pictures of two people who were lying, overturned, on charpoys [rope beds] with two transistor radios— Philips transistor radios— next to them. In subsequent years I came to understand much more about these two people. What I saw that day were two photographs of dead revolutionaries. The year was 1970, and the district was Srikakulam. They were schoolteachers who decided to leave teaching. I think about their lives and lives of others who have followed similar paths. I think about what those people could have achieved with the true empowerment of technology and other resources.” In his first month as CEO, Nadella gave each member of his management team a book called Nonviolent Communication.

For years, Microsoft “cultivated leaders who wanted to run their own show,” Nadella says. No longer. “To run the show you have to work as a team.”

For most of his childhood Nadella attended the Hyderabad Public School, an opulent institution founded to serve the children of aristocrats. Between cricket games Nadella met his wife, Anupama, whom he married in 1992. After HPS, Nadella obtained a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from the Manipal Institute of Technology. Meticulous, driven, and inquisitive, Nadella then moved to the U.S. to study computer science at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee—his master’s thesis concerned graph coloring and parallel algorithms—and work as a software engineer at Penta Technologies. After graduation, Nadella relocated to California to take a job at Sun Microsystems, which was just beginning its ascent at the dawn of the era of personal computers. At 25, Microsoft poached him and brought him to Redmond.

Nadella was “super-young, awkward, and insecure, still trying to grow into the potential he had,” his hiring manager, Richard Tait, told the Puget Sound Business Journal in 2014. But he was incredibly smart and had a deep understanding of the computer systems that businesses were using. “He was a secret weapon for us.”

It isn’t until I get to London that I finally sit down with Microsoft’s CEO. By the time I arrive, Nadella has ticked almost every box on his daily schedule: government meetings, check; keynote speech, check; educational event with children, check. I catch him leaving the offices of the Economist on an unusually warm day in the British capital. There’s a spring in his step, perhaps because he’ll be home soon. We pile into a waiting black van, and his driver takes off toward Luton Airport, 34 miles northwest of London.

I ask Nadella how this European trip fits into his broader strategy since he became CEO two years ago. He notes the tactical importance of the company’s cloud build-out in Europe and the “words and actions” needed to smooth its progress. (Once an antitrust bête noire, Microsoft can enjoy one benefit of no longer being the biggest, baddest boy on the block: a bit less scrutiny from regulators. The company is now content to let Brussels officials tangle instead with Alphabet and Facebook For its part, Microsoft is positioning its data centers as investments that support European data-protection laws.)

Nadella articulates a broader purpose to his foreign missions. “What does a CEO get to do? You’ve got to pass judgment on an uncertain future and curate culture,” he says. “For both, I feel, I learn a lot from these trips.”

That’s what Nadella does: He learns, and others learn with him. The CEO extracted intelligence in each European capital. In car rides from the airport he received briefings on how regional businesses are faring. In meals with partners Nadella got up to speed on issues in a target market. (“They’re trying to size you up,” he says. “What is this guy like? What is he trying to get done with this company?”) In closed-door meetings with officials he digested government priorities and pushed Microsoft’s interests. (“Government leaders will give it to you straight: ‘Okay, here’s your relevance to me,’ ” Nadella says.) In solo speeches he clarified the company’s priorities to rank-and-file employees.

“I’m a fundamental believer—because of maybe where I grew up—in the role of a multinational company,” he says. “You’ve got to be able to think about operating globally. If a for-profit entity is only profit seeking, then you’re not going to be a long-term profitable company. That’s kind of a paradox of business, I think.”

As is controlling the direction of a company that operates in 192 countries. I ask Nadella how he assembled his senior leadership team to spark the change he wanted to see at Microsoft. In 2015 he consolidated the company’s engineering efforts under three executives—Terry Myerson, Scott Guthrie, and Qi Lu (who has since left Microsoft for health reasons)—and bid adieu to several more, among them former Nokia CEO Stephen Elop. His resulting management team, from CFO Amy Hood to Guthrie, whom Nadella earlier appointed to replace him as head of the Cloud and Enterprise Group, comprises mostly longtime company veterans. Can Microsoft really change from within? Has its moment of clarity, more than a decade in the making, truly arrived at the hands of people who also presided over some of Microsoft’s greatest flops?

Nadella has done “a great job improving perceptions of the company in ways that can advance its agenda,” says Steve Ballmer.

Yes, Nadella maintains—if you fix the culture. “I’ve optimized for people who want to work as part of a team,” he says. For years Microsoft “cultivated leaders who wanted to run their own show.” No longer. “To run the show you have to work as a team. That’s a very different Microsoft. That’s at a premium for me.” In his chosen leaders Nadella prizes the abilities to bring clarity, create energy, and suppress the urge to whine. “I say, ‘Hey, look, you’re in a field of shit, and your job is to be able to find the rose petals,’ as opposed to saying, ‘Oh, I’m in a field of shit,’ ” he says. “C’mon! You’re a leader. That’s what it is. You can’t complain about constraints. We live in a constrained world.”

Before long I run up against my own constraints, and the van slows and pulls to the side of the six-lane highway to let me out. I ask Nadella if there’s anything I missed in my barrage of questions at 60 mph. He pauses. “I sometimes feel that business success is celebrated in much more narrow ways,” he says. “Real business success is not only surplus that you’ve created for your own core constituency but the broader surplus. After all, what is capitalism? Being able to get productivity gains that actually help the broader economy in society.”

Perhaps. So far Nadella has taken huge strides. He has managed to gain the market’s confidence and the goodwill of his own employees. His expensive push to reorient the company to the cloud rather than the desktop has proved shrewd. On the eve of his third anniversary of becoming Microsoft’s CEO, Satya Nadella is riding a hot hand—but it’s a long, daunting road back to becoming the largest and most powerful company on the planet.

A version of this article appears in the December 1, 2016 issue of Fortune with the headline “Satya Nadella’s Traveling Revival Show.”