The economic exploitation of less developed countries to benefit richer economies was a key component of colonialism. As this practice began to be seen as unjust, under the pressure of growing humanitarian movements, rich countries started providing financial aid to their colonies, for the purpose of building local infrastructures and pursuing economic development and welfare. Foreign support continued even after the colonies gained their independence, with the main intent of allowing these nations an opportunity to catch up with developed economies.

This declared purpose may lead to the mistaken deduction that developing economies are recording positive economic inflows, but this is not the case.

Some data

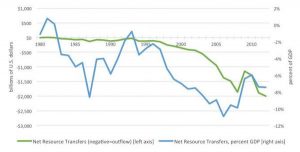

In 2012, the “global South” received a total of US$1.3tn in the form of foreign aid, investments and income from abroad. In the same year, some $3.3tn flowed out of it. Net resource transfers (NRT) for all developing countries have been mostly large and negative since the early 1980s, indicating sustained and significant outflows from the developing world.

When all the net outflows since 1980 are considered, the overall amount drained out adds up to $16.3tn.

Among the main components of these large outflows are interest payments and repatriated income on foreign investment. However, the biggest component of this leak is related to illicit financial flows, a form of capital flight mainly due to illicit practices hidden in the web of international trade:

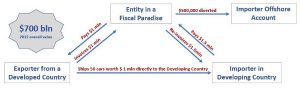

Trade misinvoicing on goods, a practice executed by corporations – both foreign and domestic – by reporting false prices on their trade invoices in order to spirit money out of developing countries directly into tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions.

Same invoice-faking on goods, a way for multinational companies to shift profits illegally between their own subsidiaries, by mutually faking trade invoice prices on both sides. The overall weight of this practice on international trade is estimated to be about $700bn per year

Illegal practices in trade in services.

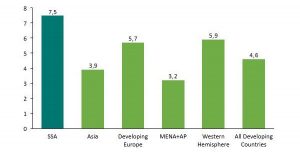

Over the period between 2005 and 2014, illicit financial flows likely accounted for between about 14% and 24% of total developing country trade, implying sizeable social costs falling on the governments and citizens of those countries. Particularly, outflows accounted for 4.6% to 7.2% of total global South trade.

Raymond Baker, founder and president of the Global Financial Integrity organisation, defined the combination of illicit financial flows and offshore tax havens as the greater driver of inequality within developing countries.

However, this inequality is not always due to illegal practices. For example, in January 2014, 14 African countries were still paying to France a “colonial debt”, a duty legalised through post-colonial agreements and meant as a tax for the infrastructure and the other benefits those countries got from French colonisation.

The aid practice itself is often mishandled. The rate established by the OECD for development aid is 0.7% of the country gross national income. However, while the UK met this target in 2013, other countries like Australia (0.22%) or Italy (0.16%) are far from reaching their required contribution. Moreover, it is estimated that around 80% of this budgeted amount is used for financing the aid structures or gets lost due to the so-called “volatility”, a euphemism meaning corruption and unavailability to lower the operator’s life standards. With aid budgets already under pressure, the negative effects of bad management may be making it even more difficult for aid programmes to achieve their goals.

Focus on sub-Saharan Africa

These financial dynamics are particularly relevant in sub-Saharan Africa.

Illicit financial outflows from sub-Saharan Africa, stated as a percentage of total trade with advanced countries only, ranged from 5.3% to 9.9% of total trade in 2014, a ratio higher than any other geographic region studied . This ratio remains higher even when averaged over 2005-2014 period.

Also relevant, sub-Saharan Africa’s assets held in tax havens grew at an annualised rate of over 20% from 2005 to 2011, a faster rate than that of any other region, either developed or developing. Today, there are around 165,000 high-net-worth individuals living in the region and owning combined holdings of $860bn in offshore tax heavens.

Finally, available data show how sub-Saharan Africa is being drained of resources by the rest of the world, losing far more each year than it is receiving: while about $161.6bn flows into the continent each year, in the form of loans, foreign investment and aid, some $202.9bn are taken out. The result is that the region suffers a net loss of $41.3bn a year.

Conclusion

Total net resource outflows from developing to developed countries accounts to about $3tn per year, that is approximately 24 times more than the global aid budget. This means that for every $1 of aid received, developing countries lose $24 in net outflows.

Rich countries should genuinely support the global South in fighting illegal trade practices and corruption, backing institutional reforms to enabling real investments, enhancing tax collection, enforcing anti-bribery rules and improving natural resources governance.

Antonio Pilogallo is an associate at Infomineo.

Infomineo is a business research company, focusing on Africa and the Middle East. The company provides its clients, including the majority of the leading global management consulting firms and several Fortune Global 500 companies, with ad hoc data on countries, markets, companies and people gathered through primary and secondary research. For more information please contact info@infomineo.com or visit www.infomineo.com.