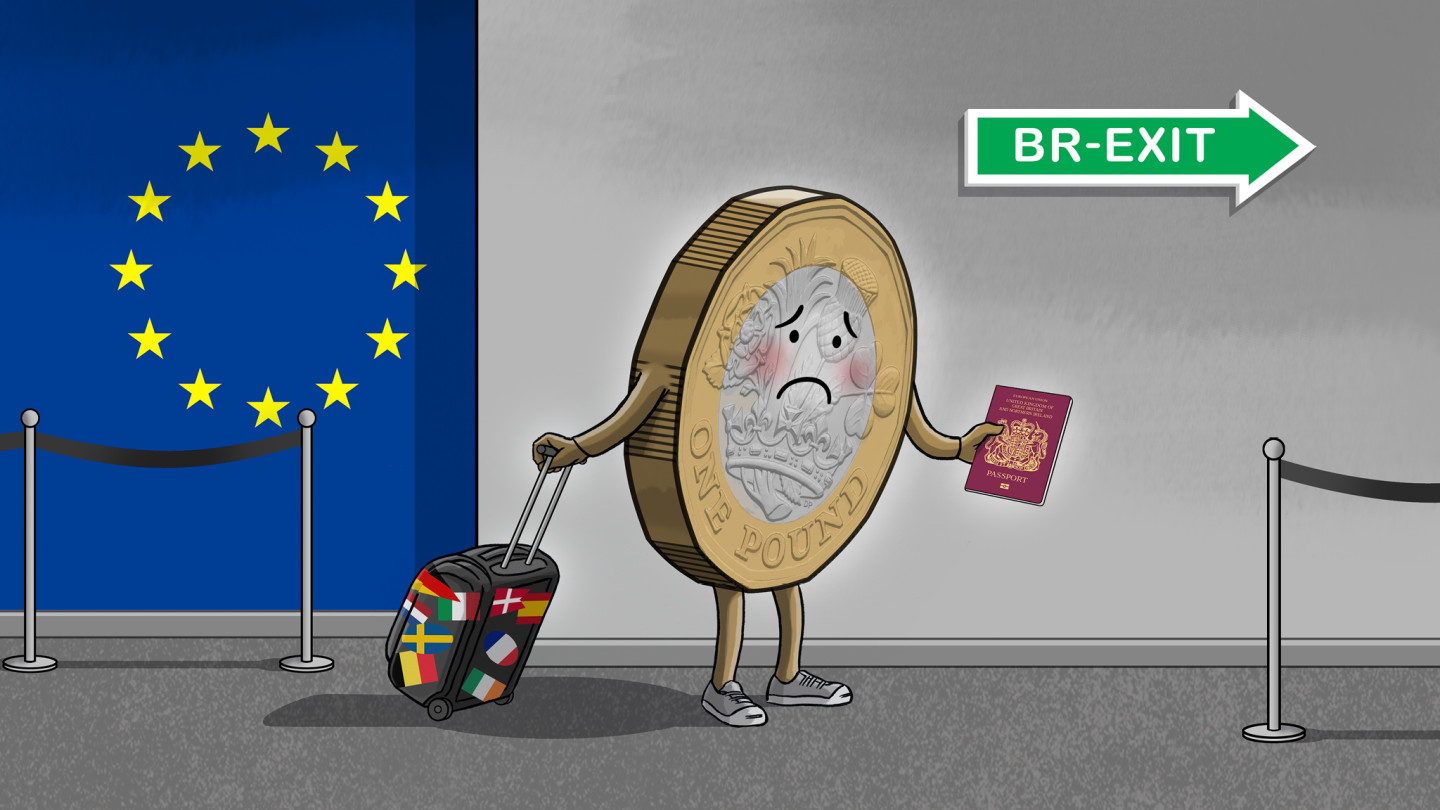

Nearly three years after the British public voted to leave the European Union, it is no exaggeration to say that a solution is no closer to being found. Indeed, Brexit looks more difficult and perhaps more distant than ever.

Theresa May has been at loggerheads with parliament for months. EPA/Mark Duffy

How did one of the world’s oldest democracies and largest economies end up in this deadlock? It’s true that the current UK prime minister, Theresa May, has a lot to answer for – but Brexit is a much bigger tale than that. It is a product of British peculiarities grafted onto European politics. It’s a story that could really only happen on this odd archipelago. It’s a very British farce indeed.

The history

If, to the outside eye, the UK’s current behaviour seems counter-intuitive, in reality, as Christopher Fear describes in his history of Brexit, it was ever thus. When the project of European integration first kicked off on the continent in the 1950s, France and Germany led several other nations into projects to pool their industrial and economic resources. The UK refused to take part.

Swayed by notions of being the plucky island nation that saved Europe from fascism, and by (very) long tales of a “glorious” imperial past, the UK had an inbuilt exceptionalism right from the start. However, just ten short years later, the six nations that had started the European Union were recovering well from World War II while Britain lagged behind economically. At that time it had become the “sick man of europe” and, by the early 1960s, it wanted into the club.

Eventually becoming a member in 1973, the challenges membership brought for certain sections of British society were on display from the outset. Many on the right liked the economic elements of the project but feared social integration in Europe. On the left, some favoured international solidarity but were unenthusiastic about the economic ethos underpinning the European project.

These matters remain central to the Brexit muddle of 2019.

The many trials of Theresa May

Given the tensions endemic to Britain’s relationship with Europe, Brexit was always going to be a difficult job. But boy oh boy, if we wanted a lesson in how not to do it, then the hapless Theresa May has given us that.

At the very start of negotiations, she drew unrealistic red lines, setting the wrong tone with the EU and leaving her entirely at the mercy of hardline Brexit supporters in her party. Most importantly, these red lines left her making promises she couldn’t keep. As Matthew Flinders, director of the Sir Bernard Crick Centre for the Public Understanding of Politics, puts it, “her political antennae were broken”.

And yet she has stuck ever more fervently to her position, to prove she was still fighting for the Brexit cause. Hence so many months of mantras, denial and repetition.

For anyone witnessing the sight John Bercow, the newly famous Speaker of the House of Commons, desperately trying to maintain order as May battled with members of parliament, there is a salutatory lesson: as in life, as in politics – even for occupants of the highest offices in the land, blindly stomping your feet and demanding the impossible gets you nowhere.

The possible trade deals

Such an intransigent and intractable approach to the Brexit negotiations has led May and the whole political class to this point: unable to agree how to leave and, crucially, unable to agree what a future relationship between the UK and the EU would look like.

By now, the question at the centre of the matter is how the UK will operate economically in the region after leaving the EU. Maria Garcia has set out the pros and cons of the five different options currently on the table.

But, it’s clear from these options that there is a problem. Each faces opposition on political grounds. As so much of the Brexit debate – on both the Remain and Leave sides – has shown, no one really had a problem with the UK’s current trade relationship with the EU. The debate around leaving revolved around emotional reasons: fears over lost imperial supremacy, over a fading national identity.

Now these emotional questions must somehow be answered with an economic model. One of the great ironies of the Brexit endgame is that the debate has been reduced to questions of trading relationships, when even the most ardent champions of free trade in the UK were happy with old relationship. If anything represents the madness of Brexit, it is the sight of politicians who campaigned for Brexit on the basis of sovereignty and “taking back control” now pushing for new economic relationships with the EU that actually cede control and sovereignty.

What is the backstop?

If the future trading relationship was an area never properly discussed in the EU referendum campaign, there was one other issue that was entirely neglected: Northern Ireland.

Northern Ireland was a disputed territory, beset by what was essentially a civil war, known as “The Troubles”, for 30 years. One side wanted a unified island of Ireland, the other side to remain in the UK. Hostilities ceased in 1998 with the signing of the Good Friday Agreement.

That agreement stated that there can be no return of a border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Of course, after Brexit that border becomes the only land border between the UK (of which Northern Ireland is a part) and the EU (of which the Republic is a member).

An invisible border works while both sides are part of the same regulatory systems on trade but becomes impossible if checks have to be made, such as on goods coming into the UK from the EU, or if taxes need to be levied.

And since all of May’s proposals so far have involved having different regulatory systems, she has had to undertake many political contortions to try to solve the riddle. Cue the famed backstop. This fallback mechanism comes into play if the two sides fail to strike a future trade deal that avoids having to have a hard border. But it effectively means the UK would stay in the EU’s customs union, which is an unacceptable compromise for many.

Whatever the form, the border question remains dangerously unanswered. It is the primary sticking point for MPs from many different sides of the debate. A question for historians will be why no one thought in any detail about what Brexit would mean for Northern Ireland – one of the major challenges in modern British history – before the vote to leave.

The delay

We’ve just learned that Brexit is to be delayed – potentially until October 31. So what happens between now and the new deadline? Despite it being clear more than ever before that May and her Brexit project is an abject failure, she, as ever, vows to carry on.

That means she might continue to push for her deal to be approved, perhaps with some endorsement from Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour opposition. The two parties are now officially in talks to find a way forward.

However, May’s seeming inability to compromise over the past few years makes this unlikely. Some hope that a fresh referendum will be held on May’s deal, potentially with the option of remaining in the EU on the ballot. Others hope for an election, though it’s unclear whether that would provide a solution to the Brexit predicament.

Whatever scenario unfolds in the months ahead, the incredible thing to note is that all options are now very much on the table – including cancelling Brexit altogether. That might seem like a very peculiar outcome indeed to the 2016 vote to leave the European Union. But then, that vote itself, and the campaign to enact it, as our experts show, has been nothing if not peculiar.

Source: www.bizcommunity.com ( This article is republished on bizcommunity.com from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.)