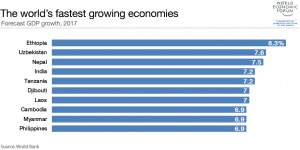

Ethiopia is the fastest-growing economy in 2017, according to the World Bank’s latest edition of Global Economic Prospects.

Ethiopia’s GDP is forecast to grow by 8.3% in 2017. By contrast, global growth is projected to be 2.7%.

The East African country’s accelerating growth comes on the back of government spending on infrastructure.

However, borrowing to finance Ethiopia’s large public infrastructure projects has led to a rise in public debt, which increased by more than 10% of GDP between 2014 and 2016, and now exceeds 50% of GDP.

Many emerging market economies have high levels of public debt, and the World Bank says it is concerned about this because it could drag down growth.

Worsening drought conditions could also affect Ethiopia’s growth, says the report.

The outlook for the world economy

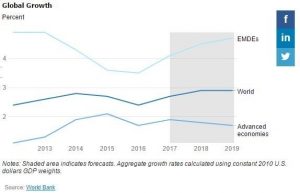

Global growth is predicted to rise by 2.7% on the back of a pick-up in manufacturing and trade, improved market confidence and a recovery in commodity prices.

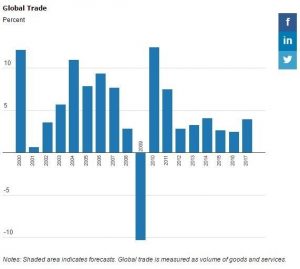

Trade increased by around 4% in 2017, up from a post-crisis low of 2.4% in 2016. Although it is expected to remain below pre-financial crisis levels.

Growth in emerging markets and developing economies

As this map shows, much of Asia and Africa (in light blue) are experiencing rapid growth.

Emerging-market and developing economies are anticipated to grow 4.1% – far faster than advanced economies.

Uzbekistan has the second-fastest-growing economy, with projected growth of 7.6% thanks to rising oil prices, benign global financing conditions, robust growth in the Euro Area, and generally supportive policies among governments of several large countries in the region.

Nepal is next, with a 7.5% projection. Nepal’s growth has rebounded strongly following a good monsoon, reconstruction efforts after the 2015 earthquake and normalization of trade with India, says the Bank.

India is the fourth-fastest-growing economy with 7.2% projected growth, thanks in part to a rise in exports and an increase in government spending.

Among the other top 10 performers are Djibouti and Laos with 7% and Cambodia, the Philippines and Myanmar with 6.9%.

China, despite experiencing a slowdown and an economic transition, was in 16th place with 6.5% expected growth, helped by robust consumption and a recovery of exports.

Advanced economies

But advanced economies are improving too. Growth in advanced economies is expected to accelerate to 1.9% in 2017, according to the World Bank.

Europe has experienced strong growth, and growth in the United States is expected to recover in 2017 and to continue at a moderate pace in 2018. Japan also saw robust growth at the start of 2017.

However, the World Bank warns that the recovery in the global economy is fragile.

New trade restrictions – such as those promised by President Donald Trump – could hamper global trade, just as uncertainty over policies could hamper investment.

Mounting public debt is also of concern to the Bank, because it says borrowing conditions – such as interest rates – could get tougher, which would affect countries’ economies.

Global government debt has risen by 12% of GDP since 2007, to 47% of GDP by 2016.

At the end of 2016, government debt exceeded its 2007 level by more than 10% of GDP in more than half of emerging market and developing economies. Fiscal balances – the ability of a country to cope with increases in costs of financing – worsened from their 2007 levels by more than 5% of GDP in one-third of these countries, says the Bank.

The Bank says that countries now need to undertake institutional and market reforms in order to attract private investment. This will help sustain growth in the long-term.

“The reassuring news is that trade is recovering,” said World Bank Chief Economist Paul Romer.

“The concern is that investment remains weak. In response, we are shifting our priorities for lending toward projects that can spur follow-on investment by the private sector.”

The pitfalls of using GDP

GDP has been has been widely used over the years to measure economic progress. But many argue that it’s not a useful indicator. Nobel Prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, IMF head Christine Lagarde and MIT professor Erik Brynjolfsson have all said GDP is a poor indicator of progress, and argued for a change to the way we measure economic and social development.

Alternatives could include measuring jobs, well-being and health. GDP also ignores the impact of important things like climate change.

Credit: World Economic Forum