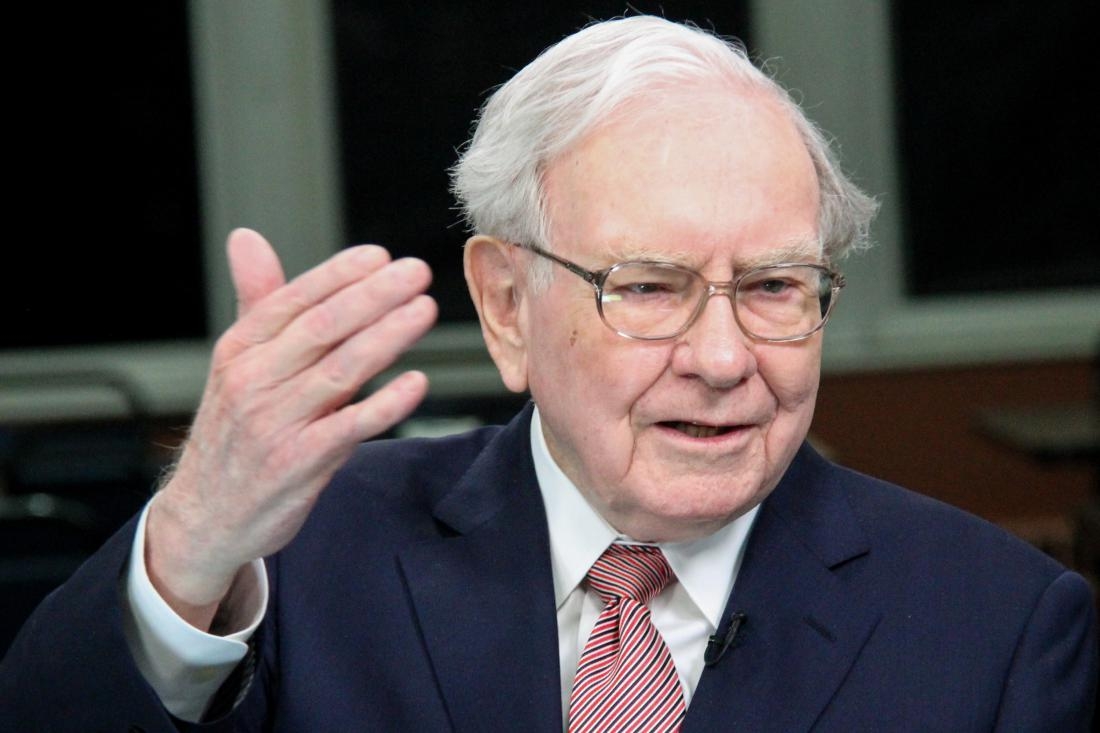

Warren Buffett has grown from a boy who at 7 years old roamed the streets of Omaha selling bottles of Coca-Cola for a nickel to a man who now sits atop the Berkshire Hathaway BRK 0% empire he created, with over $525 billion in assets.

Are you curious to know what habits enabled him to get there? Well, there are three we all can, and should, adopt.

Never stop learning

In the 50th annual letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, Charlie Munger, the longtime second-in-command at Berkshire, spoke about one of Buffett’s most enduring and important traits that led to his success:

Buffett’s decision to limit his activities to a few kinds and to maximize his attention to them, and to keep doing so for 50 years, was a lollapalooza. Buffett succeeded for the same reason Roger Federer became good at tennis.

Buffett was, in effect, using the winning method of the famous basketball coach, John Wooden, who won most regularly after he had learned to assign virtually all playing time to his seven best players. … And Buffett much out-Woodened Wooden, because in his case the exercise of skill was concentrated in one person, not seven, and his skill improved and improved as he got older and older during 50 years.

In other words, Buffett figured out what he was good at and stuck with it through thick and thin, always honing his skill.

In the book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell suggests that for anyone to truly become an expert at something, there is some element of inherent skill involved, but there is also a key component of practice. And the key is dedicating at least 10,000 hours of time to become a true expert. Gladwell asserts: “[P]ractice isn’t the thing you do once you’re good. It’s the thing you do that makes you good.”

He cites examples such as Bill Gates, who sneaked out of his parents’ house at night while he was in high school to learn computer coding, or the Beatles, who played eight hours a day in various bars across Hamburg, Germany, before they really mastered their craft.

And the same is true of Buffett, as he himself once remarked:

I insist on a lot of time being spent, almost every day, to just sit and think. That is very uncommon in American business. I read and think. So I do more reading and thinking, and make less impulse decisions, than most people in business. I do it because I like this kind of life.

In the same way, in his hit song “I Know I Can,” rapper Nas said:

Boys and girls, listen up / You can be anything in the world, in God we trust / An architect, doctor, maybe an actress / But nothing comes easy, it takes much practice

So no matter where life takes you or what you do, always remember — whether you learn from Buffett, the Beatles, Bill Gates, or Nas — while we’ll never be perfect, persistent practice will always help take us one step closer.

Patience is key

The world around us is moving at a speed that is truly hard to grasp. As The Wall Street Journal reported, “[I]t took 75 years for telephones to achieve 50 million users, while Angry Birds reached that goal in a mere 35 days.”

Another of Buffett’s distinct and admirable characteristics is his patience.

In 2003, he noted:

We bought some Wells Fargo shares last year. Otherwise, among our six largest holdings, we last changed our position in Coca-Cola in 1994, American Express in 1998, Gillette in 1989, Washington Post in 1973, and Moody’s in 2000. Brokers don’t love us.

But consider for a moment his remarks in the 2010 letter to shareholders, in which he said that for Berkshire to succeed:

We will need both good performance from our current businesses and more major acquisitions. We’re prepared. Our elephant gun has been reloaded, and my trigger finger is itchy.

It’s widely thought that means Buffett intends to purchase a single business worth tens of billions of dollars. While his trigger finger was itchy in 2010, and Berkshire’s cash pile now stands at over $60 billion, Buffett has distinctly been willing to sit on the sidelines until the right opportunity presented itself.

There is obvious value in moving quickly into something if it’s a no-brainer decision and time is of the essence, but otherwise, we would all do well to take a step back and exhibit a little more patience.

And that could be patience in buying batteries at the grocery store, or, like Buffett, the company that makes those batteries.

Give credit where it’s due

One of the final things to note about Buffett is his eagerness to commend the team of managers who surround him.

Consider his 2009 remark about Ajit Jain, who heads Berkshire Hathaway Reinsurance and is widely speculated to be a candidate to replace Buffett atop Berkshire:

If Charlie, I, and Ajit are ever in a sinking boat — and you can only save one of us — swim to Ajit.

Or his remarks about Todd Combs and Ted Weschler — who each manage a sizable stock portfolio at Berkshire Hathaway — in the 2013 letter:

In a year in which most equity managers found it impossible to outperform the S&P 500, both Todd Combs and Ted Weschler handily did so. Each now runs a portfolio exceeding $7 billion. They’ve earned it. I must again confess that their investments outperformed mine. (Charlie says I should add “by a lot.”) If such humiliating comparisons continue, I’ll have no choice but to cease talking about them. Todd and Ted have also created significant value for you in several matters unrelated to their portfolio activities. Their contributions are just beginning: Both men have Berkshire blood in their veins.

Or consider his praise for Tony Nicely in 2005:

Credit Geico — and its brilliant CEO, Tony Nicely — for our stellar insurance results in a disaster-ridden year. … Last year, Geico gained market share, earned commendable profits, and strengthened its brand. If you have a new son or grandson in 2006, name him Tony.

And the list could go on and on.

Here’s a man worth more than $70 billion, who understands that the works of others were just as important to his success as his own. So no matter where we are, we should always take the time to thank the people who helped us get there.

While we’ll always only be ourselves, adopting these three habits will help us no matter where our path takes us.

Author: Patrick Morris owns shares of Berkshire Hathaway and Coca-Cola. The Motley Fool recommends American Express, Berkshire Hathaway, Coca-Cola, and Wells Fargo. The Motley Fool owns shares of Berkshire Hathaway and Wells Fargo and has the following options: long January 2016 $37 calls on Coca-Cola, short January 2016 $37 puts on Coca-Cola, short April 2015 $57 calls on Wells Fargo, and short April 2015 $52 puts on Wells Fargo. The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.