Africa is on the cusp of a community-led socioeconomic transformation, but this cannot happen without fully integrating the informal economic dynamos of young trash sorters

In Abidjan, Johannesburg, Cairo, and other cities in Africa, young men and women make a living from collecting and recycling trash and empty bottles. Entrepreneurs like them are a common feature shaping the experience of communities across Africa, and they represent a unique opportunity for the continent’s policymakers to redesign the way in which we think about our economies.

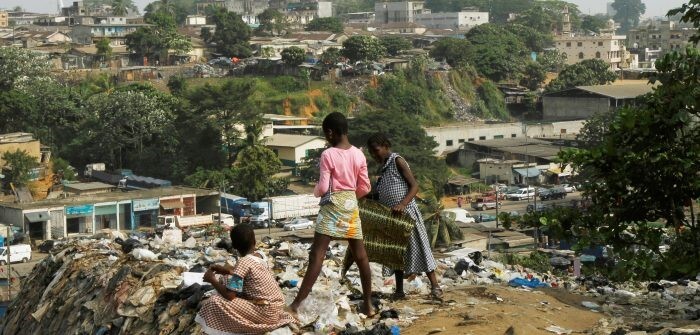

Trash Collection is a common sight

Growing up in Abidjan, the capital of Côte d’Ivoire, I would watch street entrepreneurs pass by my parent’s house—there were tailors, traders, ice cream sellers and also, trash sorters. Whenever I saw women knocking at our gate, I would eagerly run to give them empty bottles collected from our household. They made me think a bit more about the waste economy as they appeared to have clear purpose for the items we discarded. They saw value in what seemed to me to be pure waste.

They would collect the bottles and place them in large bags then lug them onto carts and transport their haul to a central location for sorting. Bottles were sorted according to color and material; green, transparent, and plastic bottles were placed in different batches.

While the collection and sorting of bottles appears to be an informal process, it actually materializes into a clear supply chain mechanism for other women trading peanuts, caramelized grated coconut, and different types of homemade juices from ginger, hibiscus, tamarind, and other local fruits. Peanuts are sold in glass bottles, juices in plastic bottles. This trade did not originate from the rubbish, but was conceived out of an opportunity to collaborate to reduce operating costs while protecting the environment. While for many of us it was not perceived as such, the fact that this supply chain process is still going on means that there is value in it.

So, the waste went from my household and many others to the streets of Abidjan to be used to trade in local commodities. Each woman recycling plastic and glass bottles received her commission from her contribution to the supply chain. And it is this interconnection between different business segments that makes the case for why we should give value to the architects of our economies.

The Business Opportunity

Women were not the only ones interested in the recycling business. Youth, learning from their mothers and sisters, took to the streets to work when the government’s trash collection service was discontinued due to a prolonged strike or had become unreliable due to changes in economic conditions.

I recall the day a young man knocked on our gate with an offer for garbage collection; I was pleased by the idea that people were in charge. The municipality had some issues with the collection process, and soon the pile of rubbish became unbearable for residents who at first self-organized to collect the garbage themselves but could not sustain their efforts or the cost. Once the community agreed to pay for their services, the young men came at regular intervals with rudimentary carts to collect and dispose of the garbage. They would come around the neighborhood streets sorting through trash and dumping the rest in their carts. As they sorted through the bins, they had limited or no tools at their disposal to protect themselves from possible disease. The process in which they engaged presented health risks, but they ploughed through the rubbish to identify elements that could be re-used in the system and resold, hitting gold at times.

For residents, when smelly and overfilled bins are not emptied regularly, they end up contributing to health problems. Yet, these entrepreneurs found an opportunity in addressing the problems created by a temporary failure of the municipality.

Without WhatsApp groups or any other digital tools, there was an agreement to invest in the business of these young men. They found an opportunity in the market and provided a solution. But their solution was not integrated into the mainstream economy. It was perceived as a temporary one while the municipality was looking for its own solutions to the garbage problem.

Nevertheless, this engagement by residents with an alternative solution created a mechanism that had become necessary. In South Africa, for example, it is estimated that trash sorters recycle 80 to 90 percent of plastic and packaging. Their contribution is valued at $53 million in landfill costs that would have otherwise been incurred. The positive health and financial impact on taxpayers is real.

As one reads about the story of trash sorters across the world, it undeniably becomes a narrative of entrepreneurship, one rooted in the heart of the consumer economy in which we thrive. In Indonesia, plastic bottles and food wrappers are complements for fuel in a tofu factory; every day, they boil 2.5 tons of soya beans—from which tofu is made. In Argentina and Chile, cooperatives such as Bella Flor, which operate within and alongside state entities, provide an opportunity for people to do meaningful work in waste management, boost their skills, and improve their livelihoods, all the while contributing to protecting the environment.

Social justice is at the heart of the issue communities are trying to address here. The work trash sorters do is a necessity for the society we created as we are unable to use existing formal mechanisms to cope with urban waste. And there is an opportunity to change the mechanism in which trash sorter-entrepreneurs have to beat the trucks to the bins; there is enough trash for all those that want to dig into it. According to the World Bank, cities will generate 3.4 billion tons a year by 2050, thus creating an opportunity to create pathways to prosperity for many more people. What is required is the acceptance that entrepreneurship in Africa is not only technology-driven. However, trash sorters may need artificial intelligence to advise them on where to get which type of trash in order to maximize their time and resources. Given the level of sophistication in the informal circular economy, the future of waste management in our African cities has already been designed.

The Entrepreneurship Hurdle

Our first challenge is to define what entrepreneurship is in Africa and what solutions can be found to the problems that are identified in the community. We know that agriculture allowed other technologically advanced communities to take full advantage of a strong economic base as means of production improved and moved up the value chain, and the level of sophistication evolved from producing raw materials to finished products.

Entrepreneurs in the United States, India, or China, for example, leaned on the capital made available from industrialists and farmers which transformed local resources connected to local, regional, and global value chains.

Agriculture, manufacturing, and industrialization created jobs, thus providing resources for investments and capital, or personal expenditure for the goods and services produced. And yet, the way Africa defines the role of entrepreneurship is often rooted in our eager aspirations which forgo the work of solidifying the base made from agricultural transformation.

Africans today appear satisfied with their ability to have leapfrogged that evolution with cellphone technology: the ubiquitous use of mobile phones in the continent has created a host of services for the users. One of the most cited is the promise of mobile money to improve the relationship between citizens and financial institutions. While this creates opportunities for technology-driven organizations, it does not solve some of our basic problems in securing better employment for African youth.

We cannot ignore the youth employment challenge while importing technological solutions from parts of the world that developed them on the back of stronger agricultural and manufacturing industries. The jobs that are available in these industries are not yet available for African youth. In essence, by failing to recognize informal entrepreneurs as solution-makers, we run the risk of not accounting for active parts of our economies.

Our economic growth can no longer ignore the fruits of youth’s labor. Measuring economic growth is not enough to determine if the African continent is advancing because these measures do not include the output of the informal economy. Trash sorters come under that category of key business actors that fall under society’s radar not because communities do not value their contribution, but because our economies are designed to account for the systems we wish we had. Although we wish for fully formal economies, most African adults are employed in the informal economy, and many of us buy their services.

From Sorting to Recycling

The second challenge is to work with communities invested in the waste management businesses to become advocates for these young entrepreneurs. The first step here is to change perceptions to consider trash sorting as worthy as any other entrepreneurial job; a starting point could be to have multiple bins in the house while we wait for the formal economy to catch up.

Ultimately, it is the respect for each citizen’s contribution to the society we want to build that determines the way in which we assign value to our fellow compatriots. A trash sorter is an entrepreneur but what value do we attach as a society to their contribution?

The steps to value addition through recycling are achievable if we see their value proposition as a business opportunity. In their own way, these young men and women conceived a business idea out of necessity, like any other entrepreneur. But the economic options offered to their business as it matures have not yet become mainstream.

Had we paused to observe the supply chain management that they had put in place, we could have developed mechanisms to buy their input into recycling plants. But we preferred the traditional large trucks with a logo which collect our rubbish to deposit in landfills.

Integrating People into Waste Management

In South Africa, Vusi Memela starts sorting trash before the cock crows. He and millions of young entrepreneurs across the continent are changing the community’s relationship with trash. Being an entrepreneur starts with an initial investment. For trash sorters, this represents a cart, a bag, and the physical and mental strength to walk around the streets of Johannesburg, or climb the hills of Sandton.

They keep fit by collecting and delivering kilometers away from the source of their trash at a pay of $6 for about 300 kilograms of cartons. However, there are times when a discarded electronic device in workable condition can increase the gains to $100. It is here we have to formulate a larger plan to integrate waste management.

In Guinea, for example, the government is working with small- and medium enterprises in solid waste management in the capital Conakry. The strategy aims at recognizing the private sector’s role in the value chain in which individuals and other groups have invested resources. This collaboration is a potential model of engagement, and the key part is the ability of private actors to create value drawing from community needs, for example, for compost and recycled metal. The opportunity for growth in the sector is enormous as the government recognizes the entrepreneurship gains brought by youth.

From Cairo to Cape Town and Addis Ababa to Dakar, white paper, cardboard boxes, white plastic milk bottles, green glass bottles, and PPC (thick plastic) are valuable. But the value cannot be limited to the informal mechanism. Tapping into the value chain of the recycling business and bringing in Vusi and his peers across the continent as trash sorters/entrepreneurs is a sure bet on employment opportunities. Being a trash sorter is not an end in itself. It is a journey into one of the key business opportunities of the present and future. In our African cities, the same will drive tech entrepreneurs to seek to change the habits of their expected customers. Why is our society not giving Vusi and his peers the same opportunity?

Digital ID and Digital Economy

The young trash sorters of Africa have started a process but like many young entrepreneurs, they cannot succeed in isolation. The market for recycling exists and will continue to grow. Through that growth, experts in recycling with hands-on experience like Vusi can create a pathway for themselves in other sectors of the economy.

Although the current view and definition of the informal sector in business terms excludes millions of hardworking Africans like Vusi from the economy, this can be resolved with technology that not only accounts for the trash collection but also for the individual’s journey into society. Their opportunity in business can be increased with a digital ID. A platform economy requires identification mechanisms for all participants and this could take the form of electronic means of payment and receipt.

But the first step in financial inclusion requires a personal identification process. In the absence of a physical ID document, there could be an opportunity to increase inclusion mechanisms for trash sorters as they register their businesses on a recycling platform. Without a digital ID and an acknowledgment of their contribution to society, informal workers’ pathways to access financial services platforms will be limited. And this is a problem in a world that makes services accessible through platforms. Logging onto the platform is not just about making money. It is about creating a system that allows individuals and their families to access government services such as healthcare and education. The digital economy thrives on opportunities for learning and development.

Ultimately, a digital ID must be more than an identification card; it should be a key to access healthcare and other basic services while unlocking opportunities for small enterprises to grow and create more jobs as the informal economy represents 80 percent of African economic activity.

While we may think that trash sorters need to be taught, we might be surprised by their ability to teach other entrepreneurs about supply chain management and negotiation skills, for example.

Recycling and trash sorters do not necessarily come to mind when Africans think of entrepreneurship, but our ability to start with what we have on the digital platform will go a long way in reshaping the continental marketplace that will unlock opportunities for more young people.

Policy for the Africa We Have

The informal economy, just like unemployment, is here to stay. While the latter is accounted for with policies designed to address joblessness, the former should be our most important focus because our socioeconomic makeup depends on men and women who are entrepreneurs in their communities.

Policymakers ignoring the informal economy are missing an opportunity to provide Africans with tools and options to enhance the kind of work that is delivering food, clothes, art, and most importantly, recycling to our communities. We have aspired to catch up with (Western) economies that formalized their processes and in doing so have left behind those that rise to take our civil servants and other workers to town. In that process, we have ignored the trash sorters who mapped the city according to the municipality schedule for rubbish collection. Those skills and that ability to beat the formal economy can no longer go unnoticed as the majority, like in any democracy, should have a say in how things are run.

For our purpose, Vusi and his peers across the continent represent a force to be reckoned with; they provide a large service to taxpayers. In Johannesburg, South Africa, an estimated six thousand trash sorters allow the municipality to save millions of rands (one dollar is 15 rands) in taxpayers’ money. But the real saving will come when municipalities fully integrate the young entrepreneurs’ skills and knowledge on digital platforms so that others can learn from them.

At the same time, these African youth could benefit from training in accounting and teaching techniques, with the end goal being the integration of their skills in teaching about entrepreneurship in learning institutions.

The final objective is not saving Vusi. It is about taking the Africa we have and showing its potential for all its 1.2 billion people. Trash is treasure in many corners of the continent. We should think about the jobs waiting for young people as we think about the economy that we have in Africa. Our economies in Africa need to account for everyone’s contribution. Starting with the ones that are improving our waste management will take us closer to achieving a community-led socioeconomic transformation.

by Carl Manlan