Successive governments’ efforts have aimed at moving Ghana’s economy from taxation to production. Has this been a myth or a reality?

Over the years, governments have implored several fiscal policies with regards to taxation with the aim of increasing tax revenue to support its expenditures. Citizens as well continuously yearn to see a time when our fiscal policies will shift from taxation to production through widening of the tax net, restructuring the fundamentals of the economy from import to export led economy as well as industrialization of key economic sectors.

Unfortunately, this “tax widening net” approach has consistently become synonymous to using consumption tax approach to get the formalized sectors to pay more tax without necessarily roping in more tax payers, and one wonders if the Ghana economy could ever move from taxation to production.

Businesses are yet to recover from the increased cost of production caused by the new tax acts arising from the July 2018 Mid-Year budget review, specifically the VAT Amendment Act, 2018 (Act 970), which reduced the VAT rate from 15% to 12.5%; the NHIL Amendment Act, 2018 (Act 971) and the GETFund Amendment Act, 2018 (Act 972) which delinked the two levies (NHIL and GETFund) and treated them as straight levies (including being non-deductible). The plight of businesses and consumers have worsened since these Acts were passed.

The July 2019 Mid-Year Budget review as expected resulted in the repeal of the Luxury Vehicle Levy Act, 2018 (Act 969), including the passing of the Communication Service Tax (Amendment) Act, 2019 (Act 998), CST which basically increased the communication service tax rate from 6% to 9%. But I keep on asking, are we ever going to move from taxation to production? Or is only good for our policy textbooks and political manifestos?

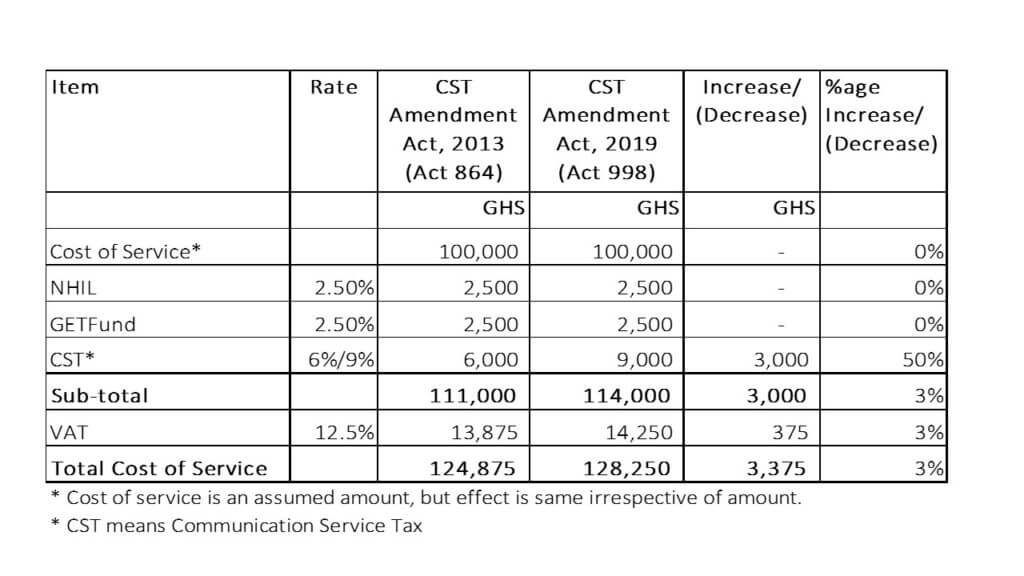

An analysis of the new CST Amendment Act 998, coupled with the VAT Amendment Act 970, NHIL Amendment Act, 2018 (Act 971), GETFund Amendment Act, 2018 (Act 972) creates more troubling and difficult times ahead for businesses especially users of electronic communication services. The table below which assumes a GHs 100,000 cost of electronic communication service to a user reveals as follows.

The analysis shows that under the existing CST Amendment Act, 2013 (Act 864), the user will suffer a communication service tax of GHs 6,000, total levies of GHs 5,000 and a VAT of GHs13,875 totaling a tax of GHs 24,875.

However, with the same amount under the new CST Amendment Act, 2019 (Act 998), the user will suffer same total levies of GHs 5,000 but CST and VAT will increase to GHs 9,000 and GHs14,250 respectively, resulting in a total tax of GHs 28,250 as compared to GHs 24,875. This means that, with the passing of the new CST Amendment Act, 2019 (Act 998) users of electronic communication services will now pay more for the same service, and with the above example, CST and VAT will increase by 50% and 3% respectively and therefore become additional cost to the users of electronic communication service, with the potential to pass the additional cost to consumers.

Nonetheless, Government will gain additional revenue of GHs 3,375 due to the increased CST rate of 9% and it is unfortunate the government’s continuous attempt to widen the tax net has rather resulted in burdening tax payers with more tax leading to increased cost of living, reduced business cash flow and eventual collapse of businesses.

And I ask again, does this tax policy widen the tax net or we are just interested in increasing tax rates no matter the cost?

Author

Desmond Aidoo is a chartered accountant and tax professional. All comments/suggestions are welcomed via dajdesmond1@gmail.com/0242844114.