The International Labour Organisation defines Child Labour as “work that deprive children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development”.

Child labour is believed to be highly prevalent in Ghana’s Cocoa Industry, with statistics suggesting an average of 2.1 billion children working in cocoa fields in Ghana and Ivory Coast (Cocoa Barometer Report 2018). Publications on the subject have cited high levels of poverty, meagre earnings of cocoa framers, poor rural infrastructure, and want of cheap labour as some of the factors fueling the practice. Reports also suggest that victims are between ages 10 to 17 years.

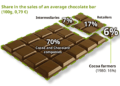

In a recent development, buyers of cocoa have agreed to a minimum price of $2,600 per tonne, as proposed by the governments of Ghana and Ivory Coast to address the perceived disparity between farmers’ incomes and money made by big commodities traders. I believe this agreement was borne on the back of constant negotiations and bargaining by Ghana and Ivory Coast in a bid to give farmers a better share of the value of the global chocolate industry. Market value of the industry hovered around USD 103.28 billion in 2017 and is expected to reach approximately USD 161.56 billion in revenue by 2024 (www.globenewswire.com).

We would naturally hope that farmers’ livelihoods are enhanced with the increment in floor price. They are expected to invest more into their farms in terms of fertilizers, insecticides, equipment, etc. We would eventually expect larger crop yield as a result of increased investments. A huge determinant however is the portion of the price increment that will eventually trickle down to the farmer. It is not automatic that livelihoods will be enhanced, the farmer’s ability to invest more into farmlands to increase production and enhance livelihood is largely dependent on how much additional income he eventually earns as a result of the floor price increment.

Venturing again into issues of Child labour, a school of thought has recommended that putting more monies in the hands of farmers will put them in a better position to hire farm hands instead of using children as farm workers. Will we see this occurrence on Ghanaian cocoa farms? I would want to discuss this recommendation in two aspects.

Firstly, for most of the instances of perceived child labour on our cocoa farms, I choose to ask why the child is present, or working on the farm before labeling the practice as child labour. Bringing to bear the Ghanaian culture, children normally assist parents with chores; at home, and sometimes in informal settings where parents work. After school, it is common sight to observe children with parents/guardians in workplaces such as food vending, farming or trading. If a child assists with work in such a setting, should it be considered child labour by international standards?

Farmers may normally introduce farming practices to their children at a young age for succession purposes. Succession in farming is now a matter of grave concern. One finding suggests average age of farmers is 50 years; and most young people in rural areas have boycotted farming and have moved to urban areas in search of “better prospects”. Some end up on streets in our cities engaging in all manner of vices. Should we not rather prop up children who show an interest in farming to promote a culture of practical learning on the farm, instead of enveloping it under the label of child labour?

We probably prefer a controlled form of ‘child-working’ condition for children on the cocoa farms, rather than to have children living on the streets. One may however argue that achieving the ‘controlled environment’ would be difficult as situations on the farms cannot be monitored 24/7 to measure the level of control in terms of gravity of work, and daily time period under which a child works. This could however be achieved through constant education in the cultural framework the farmer understands. In an earlier article I have mentioned that considering the relatively weaker frames of children and their education demands, their work on the farms should be well managed rather than a complete bedeviling of the practice, because the truth is children would continue to work on the farms!

A typical Ghanaian farmer who is considering succession for his farmland will not necessary take his children off the farm because he can afford farm hands. The child ought to be present to learn best practices at an early age, irrespective of other hands farm hands. Modern day mechanized farming is important but it does not replace the practical nitty gritty bits children may grasp when they remain on the farm learning from parents.

A research finding actually states that young people in Ghana’s cocoa belt acquire the skill of cocoa farming at very young age when they start helping parents on the farm. The skills acquired help them to contribute widely to overall farm productivity. You would not want to wait till an individual turns 18 which in effect is adulthood, before attempting to introduce skills necessary for the individual’s future.

The issue of children handling hazardous equipment on the farm such as machettes and chemicals will be discussed in a later article.

I would also stress that children learning practical skills on the farm should not normally replace formal education. Basic infrastructure should additionally be available in our rural settings to enable children attend school. Poor rural infrastructure has resulted in some children staying on farms with their parents because there are no schools in the villages.

Secondly, the argument that with increased earnings farmers can now afford to employ farm hands is largely dependent on lifestyle of farmers. Ghanaian cocoa farmers are typically the breadwinners of the extended family. For some, more earnings could mean taking up additional financial responsibilities. They would easily do this for want of praise and respect from the family. With polygamy prevalent in our traditional settings, some farmers are likely to marry additional women and have more children, which is believed to further enhance societal image. Farmers are also likely to spend more on societal obligations such as funerals, weddings, etc.

Look out for more insights into Ghana’s Cocoa Industry in the subsequent weeks.

Amma Adjeiwaa Antwi

Amma is a management consultant with M-DoZ Consulting based in Ghana. She has 15 years of industry and consulting experience. Beginning her career with an investment company in the UK, she has since served companies in various industries in the area of strategic planning, human resource development, business development, risk management, policy analysis and industry research. contact her via email on amma.antwi@ghanatalksbusiness.com