Everything about Uber is big.

The taxi app and delivery business is America’s biggest venture capital-backed company.

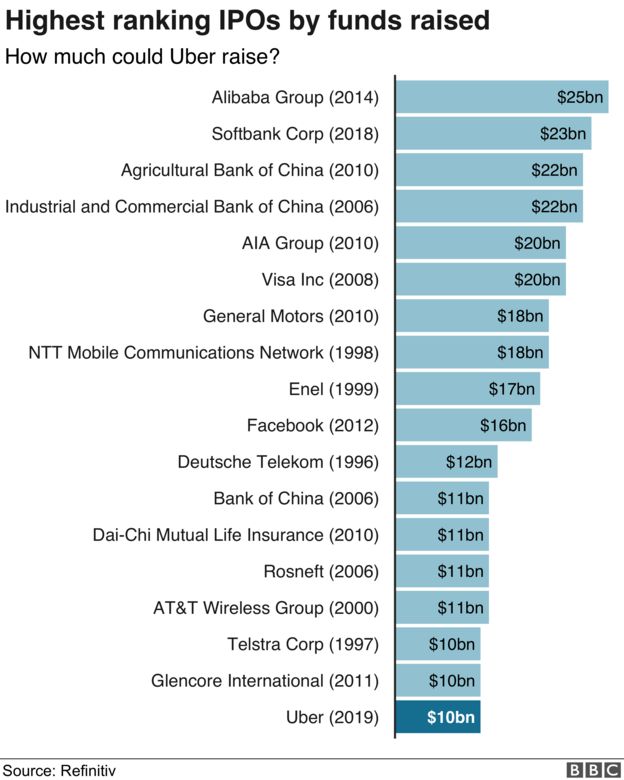

It is forecast to raise $10bn ($7.6bn) when it sells its shares on the New York Stock Exchange – one of the largest amounts on record.

And the 10-year-old company could be valued at as much as $100bn when it floats.

However, the other big thing about Uber is its losses which, although down on the previous year, hit $3bn in 2018.

And that raises the biggest point of all – when will Uber make a profit and perhaps justify that massive market valuation?

It is the question that Uber’s chief executive, Dara Khosrowshahi, will face over the next few weeks as he embarks on a roadshow to visit potential investors ahead of the flotation, which is expected in May.

What reception will Uber get?

Uber is not the first of its ilk to float this year.

Of the so-called unicorns – venture capital-backed businesses valued at $1bn or more – Uber’s closest US rival, Lyft, floated at the end of March, while online scrapbook company Pinterest is expected to list its shares next week.

But so far, those initial public offerings (IPO) have shown that there is some caution over valuations. Lyft’s stock price has fallen 15.2% since it floated.

Pinterest has priced its shares at between $15 and $17 each, which gives it a value of up to $11.3bn. However, that is still below the $12bn valuation the company had during its most recent round of private funding two years ago.

Against this backdrop, will Uber be able to hit that $100bn valuation?

Kathleen Smith, from Renaissance Capital, says: “I think sometimes they are a little bit tone deaf because they’ve been in a world where everyone has been climbing all over themselves to get to invest in their companies.

“They think then ‘oh, that means they’ll roll out the red carpet in the public markets’ – and it’s not that kind of place.”

When will Uber make a profit?

The company is unlikely to make any money soon, according to the IPO documents it filed on Thursday.

“We have incurred significant losses since inception, including in the US and other major markets,” it said. “We expect our operating expenses to increase significantly in the foreseeable future, and we may not achieve profitability.”

It expects losses to continue in the “near-term” because of higher investment in areas such as increasing the use of its apps, expanding into new markets and continuing to develop its autonomous cars division.

In a letter to potential shareholders, Mr Khosrowshahi said: “We will not shy away from making short-term financial sacrifices where we see clear long-term benefits.”

Jordan Stuart, from Federated Investors Inc., says investors are willing to be patient when it comes to profit, but only if a company can spell out how it intends to get there.

Amazon, for example, didn’t make an annual profit until six years after its 1997 flotation. Even then it took while before investors could see a sustainable path to profitability.

Mr Stuart said: “The stock really moved let’s say five or six years ago when they were really able to show ‘hey, we can turn off investment to show profitability if we want and give up top line growth for bottom line growth but we’re not going to do that’.

“Some of these companies, if they can show that scalability, that ability to turn that profit nozzle on or off, then I think investors… are going to give companies a chance to say ‘this is worth X amount of billions of dollars’.”

Uber’s sales are growing. Revenue has risen from $3.8bn in 2016 to $11.2bn in 2018.

Gross bookings from Uber’s core business – which accounts for the majority of sales – jumped from $18.8bn in 2016 to $41.5bn last year.

In its filing, Uber says it expects people to move away from the expense of owning a car to using services to get around.

Uber is also investing in e-bikes and e-scooters where it hopes to capture customers who make shorter journeys.

But investors want to see a plan.

Mr Stuart said: “I do believe [investors] have raised the bar and said ‘we’re not going to look at clicks or eyeballs or users anymore unless you can show us where is that profitability’.”

What do Uber’s IPO documents reveal?

Dan Ives, managing director and equity analyst Wedbush Securities, said the company’s IPO filing is the first time people will be able to “really get under the covers of Uber to understand the financials”.

But there are some areas of concern.

The firm’s US and Canadian business does not appear to have recovered from the #DeleteUber campaign in 2017 – not a stellar year for the company – which was first spurred by claims that Uber attempted to break a taxi strike by New York taxi drivers.

The hashtag then reappeared on social media when former Uber engineer Susan Fowler wrote a blog which alleged a toxic work environment at the company.

Uber said “our ridesharing category position generally declined in 2018 in the substantial majority of the regions in which we operate impacted in part by heavy subsidies and discounts by our competitors in various markets”.

Another potential concern is the employment status of Uber’s drivers. They are classed as independent contractors, but Uber is still facing legal issues about this and if workers were to be considered employees then Uber could face higher costs.

What now for Uber?

Uber did not specify what price it will sell its shares at – that is something to be determined over the coming weeks as Mr Khosrowshahi meets potential investors.

“A lot of technology investors are looking for is who is going to be the next FAANG,” said Mr Ives, referring to the acronym for Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Alphabet, which is the parent company of Google.

But Ms Smith said: “In light of the fact that we have seen Lyft and its very poor trading and then in seeing what Pinterest is doing tells me that investors may be a bit more ‘wait and see’ about Uber.”

Source: www.bbc.com