Senegal’s Zena Exotic Fruits (ZEF) produces an assortment of juices, jams, and cereals.

It’s been a few years since Kenyan tech guru, Ory Okolloh, talked about how Africa cannot entrepreneur itself out of basic problems. She was pushing back on the idea that entrepreneurship and innovation are the panacea for all the development challenges facing the continent. Still today, her message rings true – much more is needed to support the success of entrepreneurs on the continent – and majority of this support depends on government and private sector players.

A few weeks ago while road tripping through Togo, Benin and Ghana, I was pleased to find different “Made in Togo”, “Made in Ghana”, “Made in Benin” products throughout my journey. Whether it was chocolate, dried food products, juices or flour made from different tubers, for me it was a sign that various small scale agribusinesses are processing, branding and marketing products for local, regional and global export. Reflecting on this, I wondered what role the governments and private sector players are playing in supporting some of these small scale businesses. As recent evidence for what is possible when government support meets private sector engagement and entrepreneurial spirit, the Made in Rwanda policy has led to a 36% drop in trade deficit since 2015. What initially began in 2015 as a campaign to increase the awareness of the benefits of buying Rwandan-made products, has morphed into an all-inclusive term for interventions that influence economic competitiveness. The initiative has brought together public and private partners in the country to reach its goal.

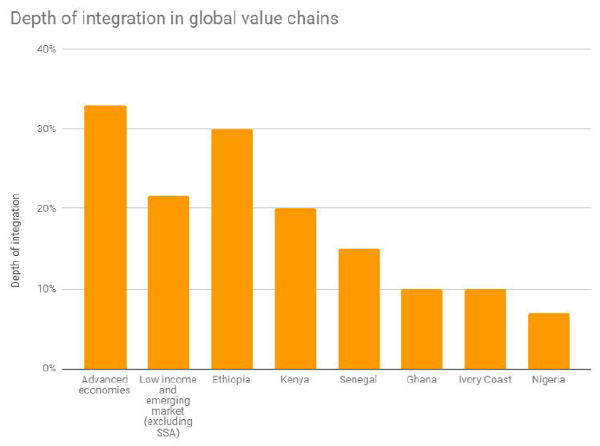

With agriculture accounting for 35% of West Africa’s GDP and 60% of the active labour force, the sector is a pivotal one for the region’s growth. West African value chains however significantly lag behind those in East Africa. A recent World Trade Organisation (WTO) report assessed the Depth of integration in global value chains, a metric that measures what the share of imported value is that makes it to a country’s exports. This is a reflection of economies’ integration with each other and with the global economy. For advanced economies this value is usually around 33% (meaning that 33% of what is imported into these countries makes it into the country’s exports i.e. value addition and conversion rather than simply importing for consumption), while for low-income and emerging market economies, excluding sub-Saharan countries, it is at 21-22%. About two-thirds of Sub-Saharan African economies fall below the average value-chain position for developing countries. An oil exporter such as Nigeria has a very low depth of integration at about 7% as their main export is crude oil and their economy is not well diversified to export much else. Across the board, East Africa outperforms West Africa in terms of how integrated their economies are in global value chains.

There are huge opportunities for increasing West Africa’s participation in regional and global value chains while also reducing the region’s import bill. As the WTO Depth of Integration report shows, “less government intervention, higher customs efficiency, better contract enforcement, and more access to bank loans significantly increase the probability that firms will participate in global value chains.”

Source: WTO 2015 report

The opportunity exists to transform the sector in West Africa and there are already signs of progress in countries like Senegal where food processing is the largest manufacturing sub-sector and has grown by 7.4% per year between 2000 and 2010. The Government’s increased investments in agriculture – totalling more than 10% of GDP per year are paying off and leading to higher productivity as production gets more specialised and commercialised. These investments coupled with strong demographic growth, a rapidly urbanising population where around 45% of the population now live in cities and a small, but growing middle class that values the convenience and variety of processed foods, all contribute to this growth. Dealing with issues along the entire value chain could enable West African countries to harness the full potential of the agricultural sector. Such efforts though need to tackle various issues along the value chain and bring together different public and private sector players who are working in the sector.

With the African food market expected to grow to $1 trillion by 2030 from the current $300 billion, and a current shockingly high import food bill of $30-50 billion, there is a great opportunity for the continent’s agribusiness industry if investments can be made in processing, logistics, market infrastructure and retail networks that can commercialise value chains on the continent. With governments already hard-pressed to finance other components of their agricultural sectors, this calls for partnerships with not only public sector players but also private sector players investing along different parts of the value chain.

We might not be able to entrepreneur ourselves out of our problems, but there are ways in which governments and the private sector can address value chain issues in collaboration with entrepreneurs for the benefit of all.

About Author

Ciku Kimeria is a Communication Advisor to the Africa Agriculture and Trade Investment Fund (AATIF). AATIF is an investment fund offering debt capital to companies and financial institutions active in the agri/food sector in Africa. AATIF aims to fill some of the gaps identified in this article through investments in small, medium and large-scale businesses along the entire agricultural/food value chain including in agricultural inputs, equipment and machinery, farming, transport and logistics, processing, export, to wholesale and retail trade. To apply for funding for your food/agri-business, access our funding questionnaire at https://www.aatif.lu/funding-application.html

Article first appeared in www.howwemadeitinafrica.com