In the eyes of businesses, the UK has come to resemble an emerging market. Our multinational clients are raising concerns around political volatility, consistent market uncertainty, an unpredictable and fluctuating currency, and supply chain issues – often the top concerns they have when it comes to investing in emerging economies. Regardless of where the current Brexit talks lead, these issues plaguing the UK are likely to remain for years.

What’s happening?

A process of political absolution is now underway in the UK. With local elections happening in May this year, many MPs feel the need to distance themselves from the inevitable poor outcome of talks. Thus, we have seen a conservative party no-confidence vote, which was defeated handily but allowed Brexiteers to show their voters that they tried to salvage Brexit. Later we saw the UK parliament massively voting down PM May’s Brexit deal, which helped MPs across all parties appear to be on the right side against a domestically unpopular proposal. Labour then got in the game by tabling a motion of no-confidence in Theresa May’s government, which failed narrowly but still serves to protect them from blame amid this Brexit chaos.

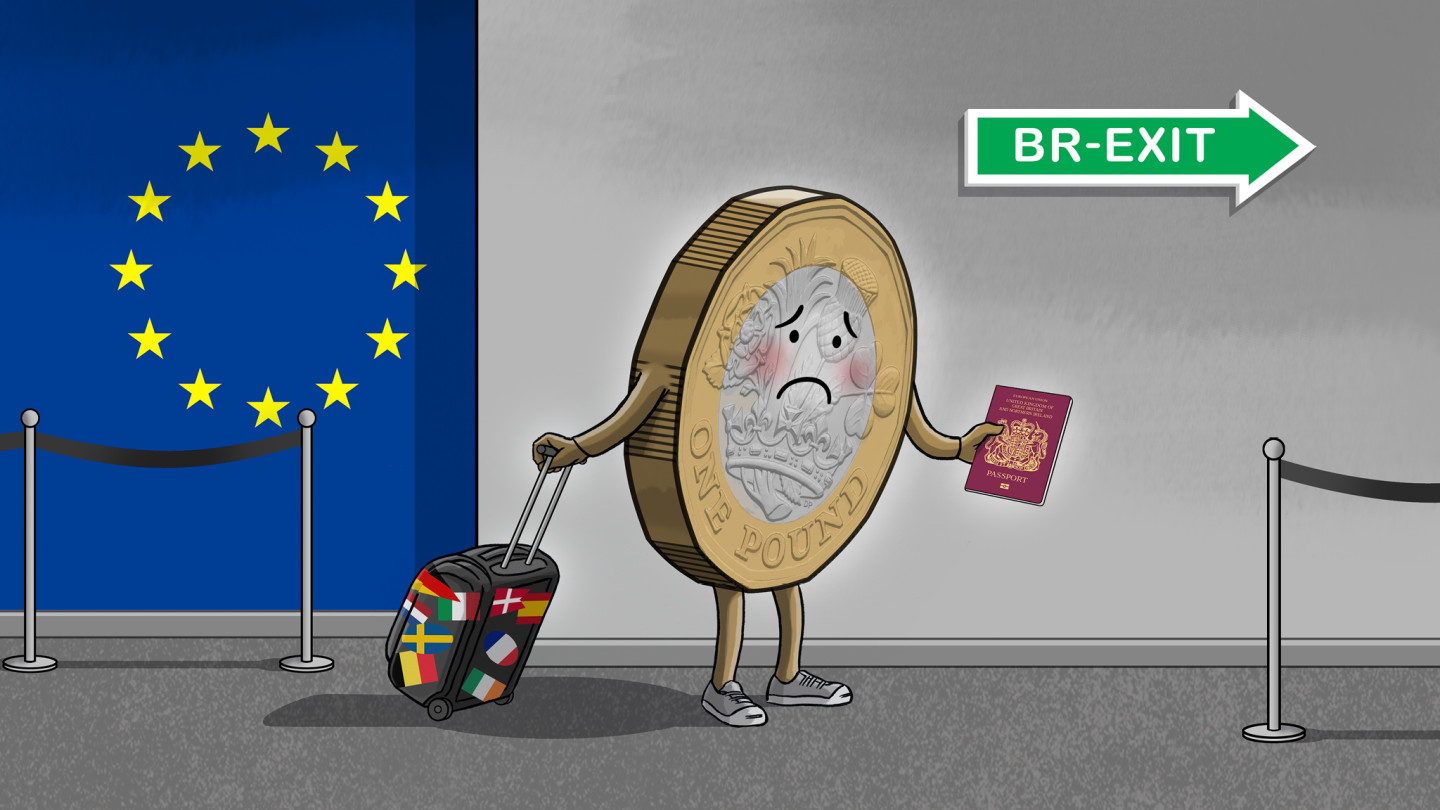

Such political volatility naturally leaves a mark on the market. The result has been pound volatility, dampened investor and economic confidence, and major concerns over businesses’ route-to-market for their products. Since the June 2016 Brexit vote, the UK pound has depreciated considerably, on the one hand slightly aiding tourism, while on the other driving an unprecedented acceleration in consumer prices, in an already competitive high-cost environment among businesses. The acute rise in consumer and business costs irreversibly hurt firms across sectors.

Foremost, fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) companies have experienced acute margin pressures in response to UK pound depreciation combined with higher energy costs, as well as increasing rent prices, labor costs, and market interest rates in 2017 and 2018. The majority of FMCG firms have increased prices to alleviate margin pressure. However, given that consumer confidence has fallen notably, and retail sales have disappointed, firms have failed to reverse the negative effect to their margins. Store closures skyrocketed in H1-2018, increasing by 30%. High street stores, especially clothing and footwear retailers, suffered, and chains such as Marks & Spencer, House of Fraser, and recently HMV announced large restructuring plans. Based on Frontier Strategy Group’s analysis, insolvencies of large and small retailers and delays in payments in the retail sector will continue in 2019, on account of elevated operating costs, weakened demand, and increased economic uncertainty.

B2B firms have suffered too. After the Brexit vote, the UK pound depreciation increased import costs for raw material and production for B2B firms. Although exports in 2017 were up due to improved eurozone demand and a weak UK pound, the export gains from pound depreciation fully faded in 2018 and costs will remain high going forward. Since June 2016, business uncertainty has not only remained in negative territory but has also deteriorated in Q4 2018 and Q1 2019, due to weakness in the manufacturing and construction sector thanks to an inconclusive Brexit future.

The unpredictability of Brexit negotiations (Will the UK be in or out of customs union?) has severely discouraged firms to proceed with large investments. Thus, business investment largely contracted in 2018. B2B firms have been increasing efforts to prepare for possible supply chain disruptions in a No Deal scenario, which would prohibit the smooth circulation of goods between UK and the EU (including Ireland) and involve huge delays in deliveries. Firms across most sectors are stockpiling products and materials used in production in order to create an inventory buffer in the event of a disorderly No Deal Brexit. We’ve heard from some businesses that they are essentially doubling stock ahead of March 29, 2019.

Brexit uncertainty is also changing the health care industry. Healthcare companies have faced higher costs for raw materials after the Brexit vote. Moreover, pharma manufacturing has weakened in 2018 in light of both slower domestic and eurozone demand. Healthcare, pharma, and life sciences companies are concerned by the discontinuance of EU funding for their R&D operations. So, when it comes to healthcare firms’ planning, supply chain and regulation exposure to Brexit are existential threats.

Most pharma companies we work with have raised the bar for Brexit contingency planning, as they had finalized plans by March 2018. The UK’s Department of Health and Social Care has erred on the side of caution and recommended pharma producers to stockpile at least six weeks’ worth of drugs to ensure smooth procurement of drugs to the NHS in the event of No Deal Brexit. The UK will continue to be a strategic hub for the pharma industry, as the healthcare industry contributes a significant share to the UK GDP, but the market has become less attractive for pharma firms to do business according to a Global Data survey in January.

Not enough companies are ready

Generally speaking, only a small majority of businesses have reacted and mostly too late. According to the UK’s Confederation of Business Industry (CBI), only 60% of companies have contingency plans in place and 40% of those companies have in fact activated them. This is inadequate.

While a No Deal Brexit is highly unlikely (and has frankly become less likely in recent weeks), the damage done to demand and the operating environment would be dramatic. This needs to be planned for. However, in reality, the deadline for the implementation of contingency plans was Q4 2018 (for most sectors) in order to be realistically ready for a severe market downturn in late March. The disconnect is odd. Companies are preparing insufficiently for Brexit yet some 80% of them also said that Brexit had already impacted their investment decisions.

There may be an explanation for this. In our experience, on average, our largest and most-exposed clients are typically the best prepared and have been for months, while those least-exposed have naturally shown the least preparation. Still, even for those latter firms this is a mistake – the market is massive globally speaking and losing market position in these times will be difficult to recover amid an only very gradually recovering economy.

The businesses that are planning are focusing primarily on supply chain and inventory management, and less on production and jobs relocation. This means mapping their supply chain in detail and identifying points of risk (e.g. transfers of products over the Irish border and also over the mainland EU border). After that, firms are creating plans for outsourcing certain production inputs that would face high tariff costs and/or alternatives for product logistics and transportation in the event of tariff and non-tariff barriers (e.g. additional paperwork, administrative costs, etc.). Particularly in the FMCG space, firms are searching for ways to increase the life of their products, whether it’s shortening time-consuming internal approval processes or substituting ingredients

These steps involve further complications. Companies need to update production systems to be more flexible, undertake stock piling measures, and sometimes even relocate business units and production. Frankly, this overhaul and its complexity can prove to be too much of an investment in time, energy, and money to undertake for businesses with relatively small investments in the UK market.

What do companies want from Brexit?

As always, businesses want predictability. Brexit is creating a market downturn, but far worse, it is creating considerable uncertainty. Firms can at least plan for a market downturn; they cannot properly plan in times of uncertainty. Ultimately, companies want to have access to the EU customs union – as before – and continuity of regulation. This involves at a minimum avoiding a No Deal Brexit, because firms have noted they are not opposed to Brexit per se but want a soft Brexit (that would include access to the EU customs union) with at least a modicum of predictability.

In reality, under the most likely scenario, a No Deal Brexit will be avoided; however, business uncertainty will be long-lasting. Simply put, there is no easy way out of Brexit talks and optimists are likely to be massively disappointed. Beyond changing the font, the EU isn’t likely to offer any substantive changes to what’s already in May’s deal that would allow it to be happily and swiftly approved by the parliament. As a result, more uncertainty is around the corner involving any of the following potentialities: an extension of Article 50, a new referendum, snap elections, and eventual New Trade Deal negotiations during an expected transitional deal. This will all naturally create further uncertainty and weaken business confidence.

What we’re seeing now is just the short-term. The full impact of Brexit has not yet been felt. We likely won’t know what the implications will be until at least 2022, after a new final trade deal is agreed to.

About Authors

Mark McNamee is Practice Leader of Europe at Frontier Strategy Group (FSG), the leading information and advisory services partner to senior executives in global markets.

Athanasia Kokkinogeni is an analyst for Western Europe and UK at Frontier Strategy Group (FSG), the leading information and advisory services partner to senior executives in global markets.

Source: www.hbr.com