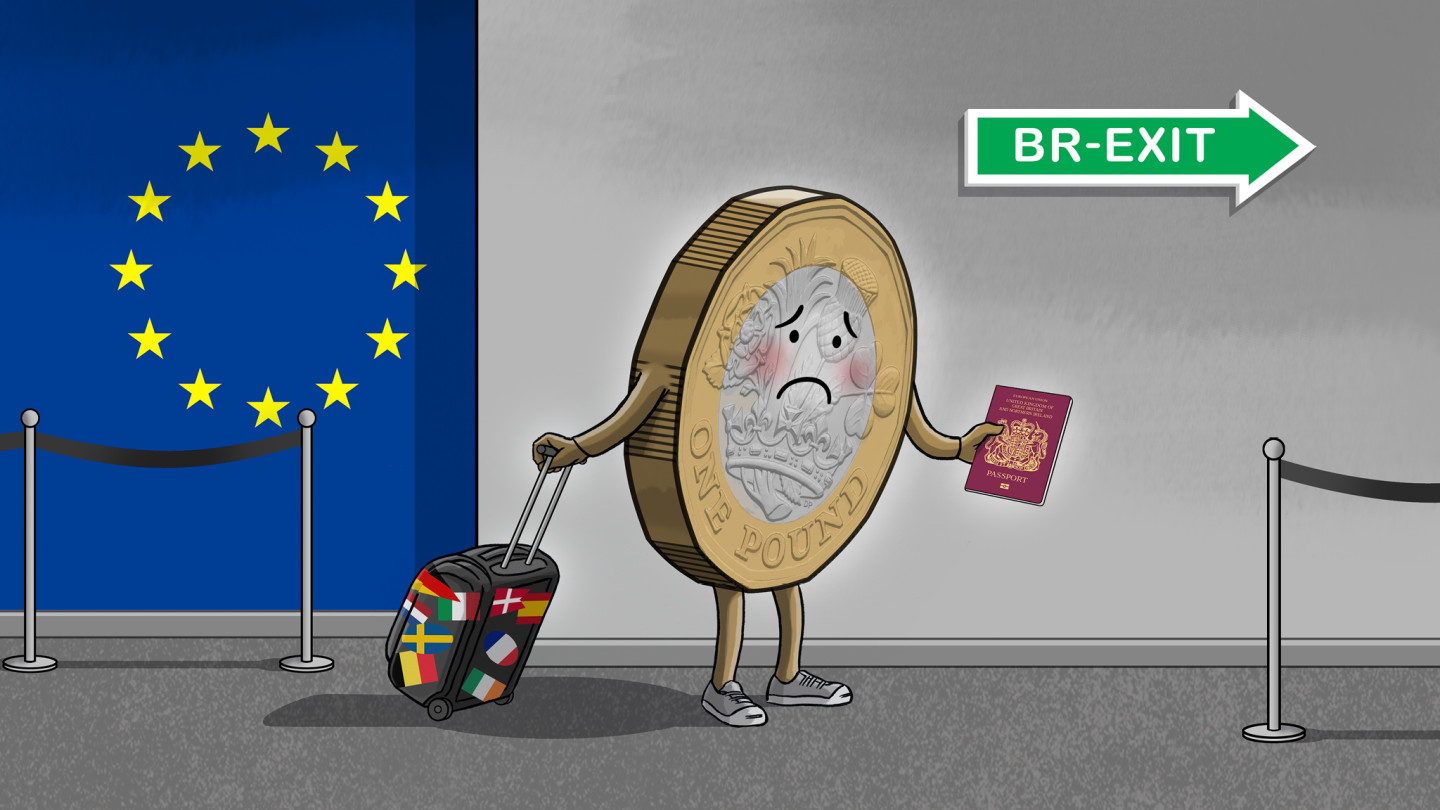

What was purported to be the United Kingdom’s most momentous parliamentary vote in a generation — the overwhelming rejection on January 15 of the ‘Brexit’ withdrawal agreement that Prime Minister Theresa May had negotiated with the European Union — has left business none the wiser about Britain’s future trading arrangements with the EU than they were before the vote.

Even assuming the exit terms are settled in the barely 70 days left before the UK’s scheduled March 29 departure from the EU, so much will remain uncertain and many of the battles fought since the referendum in June 2016 over UK-EU trading and economic arrangements will have to be refought throughout the transition period (and probably beyond given how long it takes to negotiate trade agreements).

Amid such persisting uncertainty, most UK and international companies operating in the UK are taking the only sensible course — preparing for worst-case scenarios. Given all this uncertainty, it’s worth revisiting the possible versions of Brexit and how businesses of different types could be affected by them.

Like the rest of Britain, if to a lesser degree, UK businesses are divided in their views on continued EU membership. Large exporting manufacturers, financial and professional services firms, and those needing to compete for scarce skilled or cheap labor would, by and large, have preferred to remain. So, too, UK subsidiaries of multinationals for which Britain provided an accommodating base for their EU operations.

However, small, domestically-focused UK businesses more often found EU red tape burdensome without being able to benefit from the free movement of goods, services, people, and capital across EU member-states’ borders, and thus put themselves in the “Leave” camp on the initial Brexit vote.

From the first, many UK firms’ business lobbies sought — but have still not received — an early and clear indication of the post-Brexit arrangements the UK government was negotiating with Brussels, particularly the trading arrangements, and assurances they would have a transition period after March 29 to adjust.

It is important to remember that there were two parts to the Brexit negotiations: the binding agreement covering the narrow departure terms (citizens’ rights, the budget settlement, and the domestically deal-breaking Irish border issue); and a broader non-binding document that set out the aspirations for the future trading arrangements still to be negotiated.

May’s deal would have given business a close-to-two-year transition period and a promise that EU law would be initially written into UK law wholesale so there would be legal and regulatory continuity from day one. However, her politically driven “red lines” – notably, no free movement of people and no UK jurisdiction for the European Court of Justice — ruled out post-Brexit UK membership in the EU’s single market and customs union, which the majority of UK businesses want.

This created a kaleidoscope of possible Brexits that sought to align the UK economically with the EU to the maximum extent imaginable, short of political membership. However, the major options fell along a spectrum with a “hard” Brexit at one end and a “soft” Brexit at the other.

The main points between are the so-called “Canada Brexit” towards the “hard” end, modeled on the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) on goods and agricultural products but not services, and, towards the soft end, known as “Norway-plus,” modeled on Norway’s participation in the single market with free movement of people, goods and services and a contribution to the EU budget, but no formal membership or voting rights.

May’s deal fell somewhere between Canada and Norway.

There is no majority in the UK parliament or among the voting public for any one of these models. The only outcome that commands majority support (albeit only narrowly and shrinking) is avoiding a no-deal Brexit. That is also what business sees as most disruptive as it would mean falling back to trading on WTO rules, unknown custom and tariff arrangements, and maximum legal uncertainty.

Business’s lobbying power over the May administration, which was never great, has been blunted by the increased political salience of the red lines that emerged after May lost her parliamentary majority in 2017. Her misjudgment in calling a snap general election left her dependent on the nine Northern Irish unionist MPs for a parliamentary majority, magnifying the irresolvability of the contentious Irish border issue, and weakening her ability to face down the hardest-line Brexiteers in her party.

May does not personally have strong links to the strand of conservatism that is internationally business-minded nor is she well-connected to the metropolitan elite financial services industry, which plays a disproportionately large role in the UK economy. She comes more out of her party’s tradition of moral conservatism and its shires-based support. She would be sympathetic to a populist view that Britain should not deliver a “Bankers’ Brexit.”

The degree of inter-linkage between London’s financial services firms and the economies of the EU is substantial and intricate in its regulatory and legislative interfaces. The gulf between what the industry wanted and what it looks as if it will end up with is vast. In particular, it will lose what’s known as “passporting,” the ability of financial firms to operate throughout the EU or the basis of being regulated in any one EU member state. The proposed substitute regimes for regulatory equivalence are still up in the air.

While most London-based financial institutions are not expected to abandon the city post-Brexit, many financial institutions have set up new European operations and transferred both staff and functions elsewhere to ensure they can continue to service EU clients. This includes international banks such as Goldman Sachs, Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank. Where the banks go, the professional services firms that support them will follow.

The beneficiaries have been not just European financial centers such as Frankfurt, Paris, and, in the insurance industry, Dublin, but also New York and Singapore. The long-term risk to London’s position as a financial center is that firms will develop their new businesses in their new homes. This may even apply to London’s burgeoning fintech sector.

A similar story of slow attrition and new investment going elsewhere is playing out in the manufacturing industry. Japanese multinationals including Nissan, who have built manufacturing plants in the UK as the basis of their operations in the EU, have said continued new investment can no longer be guaranteed post-Brexit.

Like many manufacturing companies in industries from electronics to pharmaceuticals, they are all at risk of Brexit-related disruption to their complex European supply chains and, longer-term, the uncertainties over the tariff and customs regimes to which they will be subject. Surveys by the Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply find that a sizeable minority of UK and EU firms are reconfiguring their supply chains because of Brexit.

Aviation is another sector vulnerable to disruption, with some of Europe’s largest airlines — Vueling, Iberia, Aer Lingus, and British Airways (United Kingdom) – at risk of having to ground their European flights because they are owned by UK-based International Airlines Group (IAG).

After Brexit, IAG could fall short of the threshold of 51% EU-member ownership, which is required to continue intra-EU flights. In the case of a no-deal Brexit, the European Commission has said airlines could operate direct flights between EU and UK cities, but inter-EU country flights and domestic flights within EU countries would be prohibited.

IAG could change its structures to become owned within the EU, but that would cause other difficulties for British Airways. In the event, the EU would likely grant IAG a post-March 29 deadline to meet its rules and avoid grounded flights in a no-deal scenario.

Also, again in the event of a no-deal Brexit, there could be uncertainty over the legal validity of insurance contracts and aircraft leasing contracts, which, in turn, could ground flights until terms can be rewritten.

Those are typical of the thousands of examples of detailed contingency work UK companies are undertaking from rewriting contracts and assessing the validity of intellectual property protections to renting extra warehousing to stockpile components and supplies and installing software to deal with additional customs declarations, estimated by the UK tax authorities to quintuple to 255 million post-Brexit.

Even here in Oxford, where BMW builds Minis at its Cowley plant, and debated hard whether to shift production of its next-generation electric-powered Minis to its Dutch plants instead, the German carmaker is bringing forward Cowley’s summer production-line close down for annual maintenance to the end of March just in case a no-deal Brexit interrupts its supply of parts.

Author: Paul Maidment is the director of analysis & managing editor at Oxford Analytica, an independent geopolitical analysis and consulting firm.

Source: www.hbr.com