Government plans to issue $300-million bond funded by diaspora

Many live on remittances as country faces economic downturn

Tunji Adeyemi traveled from Lagos to Britain seeking to persuade Nigerians living there to deposit their pounds in his bank’s vaults. Based on the crowds of people sitting at tables filling out forms in a Glasgow arts center, he’s finding a receptive audience.

The Scottish city was just one stop in Sterling Bank Plc’s push to get Nigerians abroad to open 5,000 new accounts back home this year, said Adeyemi, head of the bank’s year-old diaspora-services program. The visit late last year, which also took Adeyemi to Manchester and Belfast, winning more than 500 new accounts, is intended to boost foreign-currency revenue amid a shortage that has crippled everyone from manufacturers to airlines.

“We are ready to go all out,” said Adeyemi, who’s planning another multi-city trip, probably to Chicago and Atlanta, by April. “It’s not about having a physical branch in the U.K. It’s about your hunger and aggressiveness.”

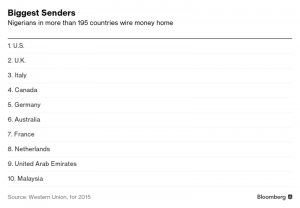

The government of Africa’s top crude producer is also trying to boost foreign currency inflows via the estimated 15 to 18 million Nigerians who live overseas. The Debt Management Office is raising a $300 million diaspora bond, First Bank of Nigeria, a bookrunner for the issue, said last week. And the finance ministry is meeting investors in London and the U.S. this week to promote the sale of a 15-year Eurobond, the longest maturity yet.

The purpose is to fund this year’s record 7.3-trillion-naira ($23 billion) budget. A decline in oil income and the exit of foreign investors have created dollar shortages, contributing to the nation’s worst downturn in more than two decades.

Unofficial Count

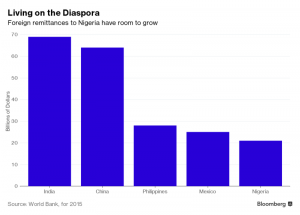

The Nigerian diaspora officially sends about $20 billion home annually, the world’s fifth-largest receiver, according to World Bank data. Based on a Sterling Bank study, remittances through informal channels may equal that amount.

“Perhaps one of the reasons we have not collapsed is because of the diaspora’s support,” said Abike Dabiri-Erewa, who advises President Muhammadu Buhari on diaspora affairs. While investment and equities slump, remittances were relatively stable as of last year, data shows.

Dabiri-Erewa’s team has drafted a policy that would commit the government to help reduce remittance fees and enable diaspora investment. And by advocating for a law that grants Nigerians abroad the right to vote, the former lawmaker hopes emigrants will have one more reason to give back.

Remittances are a lifeline in a nation where two-thirds of the population lived on less than a dollar a day in 2010, according to the most recent poverty survey by Nigeria’s statistics agency. Nigeria received 60 percent of the remittances sent to sub-Saharan Africa in 2015, says the World Bank, estimating that remittances to the region grew 3.4 percent in 2016.

Nigerian depositors abroad can transfer funds directly to relatives at home and to invest at home, both for a fee. The drawbacks are that their investments are in the naira, a struggling currency that can’t easily be redeemed for the money they use abroad.

Azimo, a London-based money transfer company, reckons that 80 percent of the wires it sends to Nigeria are for family support, which could include food, school fees and health care.

“Remittances are an injection of money into people’s hands,” said company co-founder Michael Kent. “They spend it where they think they’ll have the most impact.”

In the case of Joseph Oke, the money goes to raise cassava. A 32-year-old banking and finance graduate, he left the commercial capital of Lagos and started last year to farm the tuberous shrub on his family land, hiring two laborers in the southwestern town of Iseyin. Because he’s not profitable yet, his enterprise and his family of three are sustained by the remittances sent back by his brother, a doctor in Chicago.

“I send proposals on WhatsApp and if he approves it, he sends the money,” Oke said. “You cannot be begging money from friends so I thank God I have him over there.”

Diaspora accounts can be held in foreign currencies such as pounds, euros or dollars. Once opened, customers can use Internet banking to make transfers, convert to naira and make foreign-currency and naira investments back home.

Losing Homes

Nigerian banks are especially eager to help diaspora customers navigate the country’s cutthroat real estate market. A depositor abroad could use the bank’s services to find reliable developers, finance and purchase a house in Nigeria, for instance.

These types of accounts also afford some protection in the awkward situation where relatives entrusted with making transactions for loved ones overseas don’t act in good faith. Samuel Adewusi, a Silver Spring, Maryland, lawyer, jumped on a plane to Lagos when neighbors told him his house had been marked for demolition. A family member who’d been collecting his money and overseeing the construction project had cut some corners.

“He didn’t tell me he hadn’t gotten the building plan approved,” Adewusi said. Tracking down the building contractor who helped save his four-bedroom beach home was “like a detective movie,” but he considers himself lucky. Stories abound of people sending their savings home so family can help them build houses, only for them to find nothing on the ground when they visit, said Adewusi, who’s also chairman of board of the U.S. branch of Nigerians in the Diaspora Organization.

While Internet banking has enabled banks to provide customers abroad a new range of services, regulation hasn’t caught up. The Central Bank of Nigeria requires in-person biometric registration at banks or special centers, as well as recent utility bills at a Nigerian address. Banks get around this by encouraging customers to use addresses through which they can be reached, of family or a holiday home. They also get accredited biometric registration agencies to accompany them on their outreaches. Guaranty Trust Bank, Zenith Bank and First Bank of Nigeria are among the banks that have invested in a U.K. branch.

Nigerians living abroad aren’t going to send their money home if they don’t think they’ll get a fair deal, said Abubakar Suleiman, chief financial officer at Sterling Bank.

“They may have some element of nationality and compassion for the country,” he said. “At the end of the day, if the economics are not right, it’s very difficult to get them to make an investment.”

Credit: Bloomberg