Six months on after the Brexit referendum of 23 June 2016, it may seem that little or nothing has changed. However, one should not fall into the false sense of complacency into believing that the post-Brexit environment is and will be almost business as usual.

The undercurrent of change is already happening fast and will not only have a serious impact on the British economy, but also on the global economy. Indeed, Africa will also not be spared and the aftermath of Brexit is already unfolding slowly but surely within the continent. African countries already need to prepare for contingency plans in the post-Brexit environment.

As Prime Minister Theresa May has stated, ‘Brexit means Brexit’ and Britain is determined to break away from the European Union (EU), triggering Article 50 by end of March 2017. Remarkably, the British economy has been extremely resilient in the face of the Brexit shock.

According to the British Office of National Statistics (ONS), the UK economic growth in the first quarter after Brexit (that is the third quarter of 2016) is 0.56%, compared with the 0.51% average growth over the first three quarters of 2016. In terms of global trade, the UK traded £103bn in the third quarter of 2016, higher than the five-year third-quarter average of £93bn.

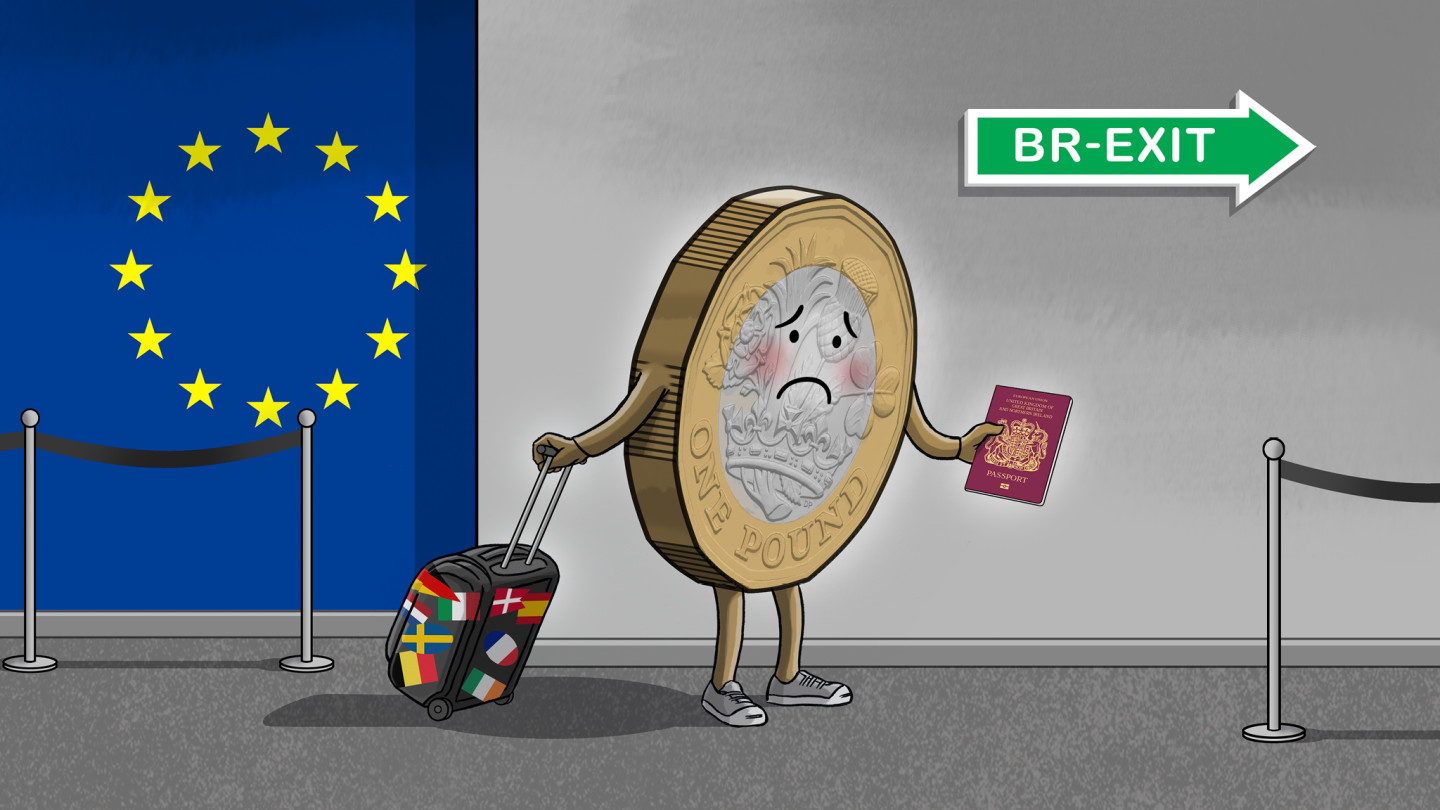

From Bloomberg data, the value of the British pound has been on a depreciation trend compared to the US dollar. Comparing the year end exchange rates over the last five years versus the US dollar, the British currency has been depreciating at an annualised rate of about 5%.

From its peak of 1.716 on 14 July 2014 to 1.2249 on 29 December 2016, the pound has depreciated by 28.62%. Moreover, just before the Brexit referendum, it was trading at 1.4707 and by 29 December, the currency has eventually depreciated by 16.7%.

The pound sterling depreciation has also had an impact on the African currencies. Data from ONS shows that most African currencies have in fact greatly appreciated against the pound, except for countries like Nigeria and Egypt where the local currencies have undergone a significant depreciation.

From June till December 2016, some of the African currencies that have appreciated the most against the British pound, are the South African rand (23.21%), Botswanan pula (18.19%), Zambian kwacha (17.73%), Tanzanian shilling (15.61%) and Angolan kwanza (15.18%). Even compared with the smallest African country, the Seychelles, the local currency rupee has appreciated by 13.67%.

The impact of this drastic pound depreciation since Brexit is that most African exports will be significantly more expensive and less competitive in the UK. As for the African exporters, this will also mean lesser export revenues in terms of their respective local currencies. This will eventually have serious repercussions on the future economic growth of the African countries.

The post-Brexit environment is bringing about a lot of uncertainties to Africa’s future trade relationship with the UK and the EU. Africa and the EU, including the UK, have been negotiating free trade deals with the Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs). When Britain triggers Article 50, many unknowns about its status and relationship with the EU will still remain. As a result, it is still unclear about what will happen to UK trade relations with Africa once it is not part of the EU; hence no longer part of the negotiated EPAs.

In terms of UK trade with Africa, ONS data show that it is on a downtrend, dropping from a peak of £32.1bn in 2012 to £19.2bn in 2015. Looking at post-Brexit data, the UK traded about £6.1bn with Africa from July to September 2016. This represents a 25.5% drop from the £8.2bn in the third quarter of 2012 and a 11.1% decline from the five-year third-quarter average figures.

In 2015, the global African goods trade is about US$928bn, according to the UN Comtrade statistics. For Africa, the UK goods trade represented about 3.1% in 2015. By and large, it will seem that the impact of Brexit on the African trade with the UK will not significantly affect the continent.

However, if we look at a more granular level, there are African countries that have significant trade relationships with the UK. For 2015, these countries are Sierra Leone, Seychelles, Mauritius, Malawi and Algeria. The UK represents about 14.13%, 8.53%, 6.09%, 4.16% and 3.85% of their respective global trade.

In terms of the UK as a major export market, the top three African countries most at risk are the Seychelles, Mauritius and Algeria. Their respective exports to the UK represented a significant 17.84%, 13.1% and 6.98% of their total exports in 2015. With the depreciation of the pound, as well as a decline in trade amount, these three countries will face a massive reduction in export revenues in the future.

Britain provides a lot of aid to Africa. According to UK Aid, the five major recipients of British aid in Africa are Ethiopia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, South Sudan and Tanzania. In 2015, they received £339m, £263m, £218m, £208m, £205m respectively. But with Brexit and budget tightening measures, the UK government will provide significantly less aid to Africa in the future.

In 2015, the UK government spent about £2.1bn in terms of aid to Africa. By 2019, the overall UK aid to Africa is forecast to decrease by more than 60%. Some of the countries that will be severely affected by this reduction are Malawi, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Uganda and Zimbabwe. These countries will experience a drop of about 80% of UK aid by 2019.

Last, but not least, Brexit will also affect UK investment in Africa. According to ONS data, the UK’s stock of foreign direct investment (FDI) in Africa was £42.5bn in 2014. The three former British colonies – South Africa, Nigeria and Kenya – were the major destinations for these investments.

The net FDI flow from the UK to Africa has been about £1.7bn, £3.2bn, £2.5bn for 2012, 2013 and 2014 respectively. But for 2015, there has been a negative outflow towards the UK of £190m. With Brexit uncertainties, investment may be put on hold until there is better clarity in terms of the UK’s status in the world, as well as its future relations with African countries.

So far the impact of Brexit on Africa has been mainly on currency exchange rates and trade. In the medium and long term, UK foreign investment and aid will also be affected. The future of the UK-Africa relations will eventually depend on how Britain navigates through the highly volatile political and economic environment, when it will invoke Article 50 by the end of March 2017.

As for African governments, they should already start preparing contingency plans, irrelevant of whether the UK is their major trade and investment partner or not. This is because the world will face an extremely volatile environment, once Article 50 is invoked. Those African countries prepared for the worst case scenarios will be the ones in the best position for future economic success.

The author, Richard Li, is a partner of Steel Advisory Partners, Singapore. This article was written specifically for NTU-SBF Centre for African Studies, a trilateral platform for government, business and academia to promote knowledge and expertise on Africa, established by Nanyang Technological University and the Singapore Business Federation.