All the way up to the university levels, many of today’s teachings stifle both understanding and skills building. The point is simply this, where there are no practical connections to the subjects being taught, there cannot be any appreciable commitment by the learner. And where one can’t develop the skills to apply what is learned to create anything useful, what then is education for?

One can be taught till kingdom come – one can learn the multitude of theories till yet another kingdom appears – and still remain stuck, unskilled, unproductive, and unfulfilled. A good many academic degrees are not grounded in practice; they float aimlessly with the wind. That is the misery passing for education in parts of Africa, hence the underemployment and persistent poverty.

And for some unfathomable reason, the very same academicians leading and looping those vicious cycles are the ones expected to resolve the dilemma!

In the column, “Avoiding the miseducation of Ghana’s youth”, I posed the following: “Why have dreams if you can’t live them? Why have interests or curiosities if you can’t pursue them?” Education has quality only if it fosters one’s skills to innovate, to create, to invent, to produce a needed product or to be employable to add value to an existing entity by helping to solve problems.

These days, it’s so important that educational assessments are not merely based on ticking off right answers on examination sheets or writing reports that nobody may use. Project based learning – starting from the primary levels – offers the best opportunities to apply what one learns, to be creative, to develop a product, or a service that puts one in a better stead.

In John G. Maxwell’s book, “The Winning Attitude: Your Key to Personal Success”, he noted that “it is more difficult to learn something wrong, unlearn it and re-learn it, than to learn it correctly the first time. That is certainly true about our attitudes. Those things which we feel and accept at an early age have a tendency to hang on tenaciously even when we know better and desire to change. The first impressions upon our lives are not the only impressions, but many times they are the most lasting.”

The economist (June 25, 2016) cited the example of Olin College, an engineering university in Needham, Massachusetts, where “During their four years, students complete 20-25 projects … They spend about four-fifths of their time in teams and combine ideas from different disciplines.” In addition to the variety of practical skills learned from those hands-on experiences, the “projects strengthen recall and hone communication skills” and prepare graduates for employment or to strike out on their own as entrepreneurs.

The instructors there are “hired for their teaching expertise rather than publication records” or academic over-specialisation. The college “has received visits from 658 universities from 45 countries keen to learn about its approach.”

The weekly cited also the Aalto University (Helsinki) that “brings engineering, art and business students together to design, build and market a product” by bringing “theory and practice closer together [to] spark young people’s curiosity”. Such universities promote an entrepreneurial environment and they hire instructors for that purpose.

Worldwide, education is being re-designed to reflect the practical needs of the times. In Ghana, as in other parts of Africa, theory and practice must today be fused at the hip like Siamese twins: and that is where our traditional universities and their lecturers must rise to the occasion, and be up and doing.

A reader once commented that “Our leaders should look at the top level problems again. Education has changed from grammar to skills. People should be multi-skilled in different professions to stay competitive in the future world. We cannot continue to let young adults stay home because they failed in English or Science … Rather than invest in infrastructure to expand admission and learning opportunities, we kept the same infrastructure and then restricted access by contriving high failure rates … In an environment of repressed growth, this created the perfect storm for persistently high youth unemployment.”

In Ghana, the National Accreditation Board (NAB), for example, needs to appreciate one key thing: that Ghana’s prosperity depends on the practicality of education; that is, the practical solutions to the nation’s problems. With that sound measure, many traditional “chew, pour, and be poor” universities may themselves need alterations or falter. We are not in the year 1948 where the purpose of the traditional university was to train civil servants for colonial government employment, where individuals and local industries were forbidden to compete with the colonialists. Those years are long gone.

The NAB systems of monitoring must evaluate in equal measure the efficacy of both the public and private universities; they must not lose sight of the fact that we live in a world where new insights are spawned daily and conditions are in a permanent state of flux, constantly changing. To remain dynamic and relevant, they must discern what works and what doesn’t.

It takes guts to push boundaries and allow some fresh entrants to experiment with bold and relevant approaches to educating the nation’s youth for better results. Aware of the tyranny of the status quo – that is, guarding against doing the same things and expect different results – they must discern the differentiation most appropriate for the occasion. They must prompt and support the new normal, and thereby sway from rigidity, sway from a herd mentality where requirements remain fixated.

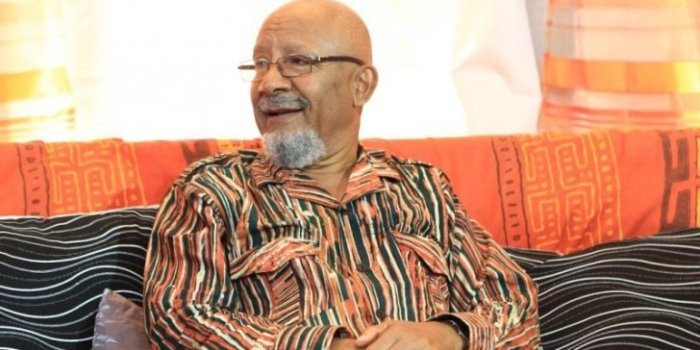

Author: Anis Haffar

He attended Mfantsipim School, Cape Coast (Ghana) and earned a degree in Business at California State University, Los Angeles. He did his graduate work at the English Department, and the School of Education at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona for Licensed Teaching Credential in English … more here

(Email: anishaffar@gmail.com )