As the fireworks explode in clusters over the lagoon in Abidjan, the great grandchildren of independence-era leaders Kwame Nkrumah and Félix Houphouët-Boigny clink champagne flutes and move to the dance floor.

Across the other side of the ceremony hall, the ink is drying on a document that dissolves the borders between the two countries. Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana are officially one country. Visiting dignitaries applaud from surrounding tables. This imaginary scenario should make Ghanaians happy.

The union could help bridge the Anglo- Francophone divide in the sub-region

Côte d’Ivoire, our neighbour to the west, recovering from a dreadful war, could this year grow its gross domestic product by almost 9%. Meanwhile we, relatively stable for more than 30 years, will be growing at less than 4%. Côte d’Ivoire, Togo, Benin, Senegal and the Democratic Republic of Congo were included in the World Bank’s 2015 list of top 10 reforming countries for business competitiveness, but Ghana was missing.

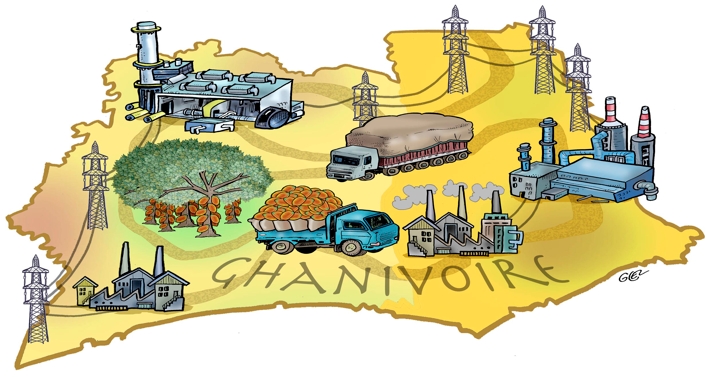

Assuming a hypothetical scenario in which people and goods could cross freely between Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, many revolutionary things would be possible. A domesticated global centre for cocoa would come with the ability to determine prices and control production – creating an OPEC of cocoa, COCOPEC. This could leverage the ability of the two powerhouses to attract investment in processing plants, with significant opportunities for job creation.

Whereas both countries dominate what is estimated to be a $9bn-per-year industry, a new joint country could make giant strides into the high-end chocolate industry, which is estimated to be worth $87bn a year. This would lead major players such as Mars, Nestlé and Cadbury to relocate some of their production facilities from North America and Europe.

Embarking on this value-addition drive, as opposed to being mere suppliers of both primary and intermediate products of cocoa, would require a larger consumer market. As West Africa’s second- and third- largest economies and with burgeoning middle classes, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire together could exploit their growing consumption of chocolate to attract investment in this segment of the value chain, as well as sell to the Nigerians.

Next, we could become a regional power-house for energy production, distribution and marketing. Both countries are already making huge public investments in energy infrastructure. And with large deposits of oil and gas, there is an opportunity for expanding manufacturing and port facilities to handle cargo for landlocked neighbouring countries.

Côte d’Ivoire has West Africa’s most reliable energy infrastructure and has set its sights on increasing production to export to countries such as Guinea and Sierra Leone. Ghana has similar ambitions.

The net effect of reliable power supply – not only for increasing domestic demand but also for export to other West African countries – is that the duo could be the energy hub for West Africa. This obviously would have an effect on investment and subsequently industrialisation.

It promises to place these fused two countries at the epicentre of economic activity within West Africa, just like South Africa is the bedrock of Southern Africa.

We could also create a financial services hub to rival South Africa’s. Côte d’Ivoire is back to becoming the most favoured destination for multinational and supranational financial institutions, with a regional bourse and regional central bank. Meanwhile, Ghana is perfecting the art of providing unique financial services to English-speaking West Africans.

The growth of the two markets could mesh with Nigeria’s relatively deeper financial sector, which provides tremendous opportunities for growth and development. The creation of a sub-regional bond market, for instance, could provide governments and businesses with significant funds to undertake infrastructure projects.

The success of such a measure would also benefit smaller West African countries that are otherwise not able to participate in international bond markets. A well-integrated financial system between the two countries would boost trade and economic activities.

Cultural exchanges through language, music and food would not only provide economic returns through tourism but also serve as the basis for a special relationship that guides the resolution of disputes. Such a cultural exchange already exists to a large degree between Nigeria and Ghana, with Ghana seen as Nigeria’s little brother, and this has had enormous benefits to both countries. As the citizens of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire become even more integrated, this would guide policymakers in their decisions relating to each other.

The benefit would extend to the entire Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), as the union between these two countries could help bridge the Anglo-Francophone divide in the sub-region. Acting as a venue where the French-speaking and English-speaking countries of Africa could meet and discover each other, the newly combined Ghana/Côte d’Ivoire could also finance these matchmaking transactions, a potentially huge new source of growth.

In particular, the new country could help the ECOWAS sub-region speak with one voice. It would provide leverage for countries – including the regional powerhouse Nigeria – that have relatively developed political and democratic institutions to press other West African states to adopt additional democratic and good governance principles.

The integration of these two countries could also bind Nigeria into ECOWAS more firmly, which is one of the key issues facing West Africa. While it represents 77% of ECOWAS gross domestic product, Nigeria does not trade much with its neighbours – something a new Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire would help to fix.

For all this to happen, however, there would be much work to be done. First, a head count. Politicians believe in the numbers game and swear by any means to ensure the right numbers are voting for them. This would mean that only eligible citizens of a country should in fact vote for a leader.

So, even if borders as we imagine them here are virtual, identifying legitimate citizens would not be subject to any negotiation. This means that Ghana, for example, would be jolted into making sure the issue of identifying every Ghanaian becomes not just a technology issue but a development one, as public services and foreign direct investment would have to be based on credible statistics.

A second area of attention would have to include real attempts at devolution to soften the blow for two sets of national leaders who would necessarily cede power in a new configuration. Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire operate presidential systems of government with a very powerful presidency usually aided by a majoritarian parliament, creating a very centralised state that feeds on patronage and cronyism.

Finally, this imagined, new West African state would require a transformed public service. The disproportionate balance between politics and policy – with the former dominant at almost all levels of government in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire – means that the current speed of public-sector reform is dramatically and frighteningly slow. This deters our progress towards the objective of becoming upper-middle-income economies. We will need to see growth in overall national capacity, and that national capacity must be anchored on a public sector with a strong attitude in support of reform and without the long, invisible but debilitating arm of politics.

Author: Franklin Cudjoe is the Founding President of Imani-Ghana.

This article orginally appeared in The Africa Report Magazine