The purpose of this article is to identify and acknowledge the strong resurgence in Ghana’s economy since the election of President Nana Akufo-Addo in December 2016. The cases mentioned are by no means presented as an exhaustive list, but as indications of steps taken and instances noted of improvement by the Government in Ghana.

It must also be said that Ghana has in some instances been the beneficiary of events beyond its control or actions beyond its intention. The article will also identify challenges facing the country. As a point of departure, it can be said (and is said by many) that Ghana and its economy reflects the full advantages of a stable and mature political system/environment.

Economic growth improvement

When President Nana Akufo-Addo took office in January 2017, Ghana was in a somewhat bad spot. Economic growth had slowed down to just 3.7%, and inflation and unemployment rates were rising. More and more young people were leaving Ghana and going broad. Corruption had become a disturbing issue. Akufo-Addo promised one factory per district, free secondary education, more investments from abroad, and the curbing of corruption.

One year later, the results are quite positive. According to the World Bank, Ghana will be Africa’s fastest-growing economy in 2018 with a growth rate of 8.2% (some say 8.3%) as a result of increased oil and gas production, which boosts exports and domestic electricity production. Ghana is also forecast to the world’s fastest-growing economy for 2018.

Initial estimates for Ghana’s growth for 2017 came in at 7.9%, an incredible improvement relative to that of 2016. However, the statistics office of Ghana announced in April 2018 that its economy actually expanded at 8.5%, an even better performance than initially envisaged. Inflation dropped significantly. End-period inflation was 11.6% in October 2017, compared to 15.8% at the same period in 2016. The overall budget deficit was 4.5% of GDP in September 2017 against a target of 4.8% and compared to 6.4% in the same period in 2016.

According to KPMG, the industry sector in Ghana recorded the highest growth of 11.5% in 2017, compared to 1.8% in 2016, mainly from mining and petroleum. The agriculture sector grew by 7.6%, up from 5% the previous year, driven by good performances in the crops, fisheries, and cocoa sub-sectors. Growth in the services sector, however, slowed to 3.7% from 6.6%, due to slower growth in the information, communication, and finance sector.

The services sector is the biggest contributor to GDP, accounting for 57%, followed by industry with 24% and agriculture with 19%.

Ghana’s economic growth followed the consolidation of macro-economic stability and implementation of measures to resolve the crippling power crisis. Its continued recovery in 2018 will depend on fiscal consolidation measures remaining on track, the quick resolution of the power crisis, two new oil wells coming on-stream, and an improved cocoa harvest and gold production.

EU interest in Ghana

In addition to the excellent GDP growth, the EU announced plans to use Ghana’s market as a target to reach the other countries in the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) region. The EU is working closely with Ghana to further diversify and expand the country’s production and exports, particularly in the agriculture sector where Ghana has much potential.

Ghana and the EU signed four financing agreements, totalling €175m (US$216m), to support various priority areas for the government in terms of job creation, service delivery and better financial management. The government was committed to build a strong agro-based economy that would support the industrialisation agenda in line with the “One District, One Factory initiative”.

In another initiative, Zeepay, the fastest-growing mobile financial services company in Africa, have received a grant from the Swiss government to improve mobile remittance services from the diaspora. The fund’s focus is to assist the partners to deepen remittance services in a bid to improve financial inclusion over the next two years. According to Zeepay, the grant will enable them to launch Remitinvest to drive remittances for investment into Ghana. This would assist immigrants greatly as they would have a window to save in Ghana. The managing director of Zeepay saw this as a significant milestone as European governments are starting to recognise the plight of migrants and their contribution to national economy building.

China and Ghana

Ghana and China have signed an agreement for the construction of the Jamestown fishing port complex. The $50m project is expected to commence this year (2018). When completed, the project will increase the productivity of the fishing sector and create about 1,000 job opportunities for the youth in the community. A $16m bilateral agreement was also recently signed for the implementation of various projects.

In addition to the Jamestown project, phase two of the University of Health and Allied Sciences will be funded by the Chinese government. China will also support a feasibility study for a cocoa processing project in Ghana’s Western region, while it has begun with the donation of police vehicles and equipment.

Last year, economic and trade cooperation between the two countries grew strongly as bilateral trade reached $6.67bn, an increase of 11.7% on 2016. China is Ghana’s largest trading partner and Ghana’s export to China surpassed $1.85bn in 2017. China’s financial investment in Ghana last year reached $123m, covering 25 projects, and its number of projects ranked top among all the foreign investment countries in Ghana.

According to Ghana’s finance minister, the Ghanaian government is committed to ensuring that the necessary structures are put in place to propel economic growth, as well as pursue the “Ghana Beyond Aid” agenda. China in turn hopes the projects will improve the infrastructure of Ghana and increase the driving force of Ghana’s economy.

China was also quite clear that it did not attach any political strings to its aid to Ghana. They also fully supported the “Ghana Beyond Aid” initiative of the Ghanaian government, stating that they wished that this aspiration would be achieved with the support of international partners.

Investment rankings and opportunities

In Rand Merchant Bank’s 7th edition of Where to invest in Africa, they ranked Ghana at fifth place. RMB indicated that Ghana slipped from fourth to fifth place due to perceptions of worsening corruption and weaker economic freedom. However, it seems that the EU does not have the same views. Also, Ghana’s commodity resources in the mining sector, as well as its oil and gas reserves, must not be underestimated. Its new president, President Nana Akufo-Addo, is also seen to be having a positive impact in his country since his election in 2016.

Ghana does not fall into the top 10 countries of the World Bank’s ease of doing business rankings in Africa, only coming in at 12th place amongst sub-Saharan Africa (14 when North Africa is included). It must address this as a matter of urgency as it could deter potential investors.

However, in spite of recording strong growth in 2017, Ghana recorded one of its biggest drops in the latest World Bank Doing Business Report, with the data showing its ranking fell by 12 places from 108 in 2017 to 120 in 2018.

The data showed that Ghana dropped in most of the indicators that the World Bank reviewed in the assessment. Despite these challenging results, Ghana was praised for increasing the transparency of dealing with construction permits by publishing regulations related to construction online.

Despite Ghana’s significant drop in the Doing Business Report, it still did better than its peers in West Africa. It took the top spot as the best place for doing business in the sub-region, beating Cote d’Ivoire (18), Senegal (19), Nigeria (22), and Gambia (23).

Government sources are hopeful Ghana would improve a lot in the 2019 rankings, given the reforms that they have undertaken. Since the first quarter of 2018, government has introduced a paperless system at the ports, and reforms implemented so far to aid business registrations, would improve the business environment significantly.

Despite this drop in the rankings, Ghana still remains the preferred place for doing business in the region, because of its stable political environment.

The mining sector’s contribution

Ghana’s mining industry could be the beneficiary of higher investment levels given the government’s efforts to improve the business environment and key gold mines preparing to reopen or expand operations.

In February 2018, AngloGold Ashanti from South Africa announced an agreement with the Ghanaian government to redevelop the Obuasi mine in the south of Ghana. They will invest between $450m and $500m over the next two and a half years to develop the mine into a more modern, mechanised operation. In return, the mining firm has been granted tax concessions and a security force to guard against the challenge posed by illegal mining. The project is expected to generate between 2,000 and 2,500 jobs.

In early March 2018, Australian company Azumah Resources expanded operations at its Wa Gold project in Ghana’s north-west. In total, the Wa Gold project holds an estimated 2.1 million oz of minerals.

South-African firm GoldStone Resources has also outlined plans to reopen a mine they own.

The renewed mining activity comes amid government efforts to attract more investment to the sector, a key growth driver for the economy. As the world’s 11th-largest gold producer, Ghana generated $5.8bn from gold exports in 2017, up 17.6% from 2016.

In order to improve the business environment for producers, government reduced energy tariffs by between 10% and 30% for various categories of consumers. Mining firms could save around $2m-$3m per year as a result, significantly lowering the cost of doing business and attracting more players into the market.

In order to improve governance in the mining sector, Ghana transferred the assessment and valuation of gold exports to the state. Previously, private companies were responsible for grading their own gold, and the lack of oversight led to concerns over incorrect valuations of the commodity.

Ghana’s improved economic situation could also be a factor encouraging increased investment. The World Bank forecasts growth of 8.3% this year, the highest in sub-Saharan Africa and the world, while a drop in inflation, stabilisation of the cedi and a reduction in the fiscal deficit are expected to further improve investor appetite.

Oil and gas in Ghana

Given the long timelines associated with oil and gas exploration and production, the current government can hardly claim any credit for the developments in this sector. However, their willingness to create a business-enabling policy environment has stood the sector in good stead.

Ghana is a relative newcomer to the oil sector, highly committed not to scare foreign investors away and keep existing covenants intact. 2017 saw Ghana propel to an upward curve, leaving behind the tribulations of 2015 and 2016, not only because new projects are coming online (currently only three offshore fields are producing), but also because Ghana has managed to peacefully resolve its maritime boundary dispute with Côte d’Ivoire. The 2016 presidential election also produced little to no change in Ghana’s energy policy, further consolidating the country’s appeal in investors’ eyes.

Oil production at already exploited fields is expected to ramp up rapidly, surpassing a government-anticipated average of 123,416 barrels per day (it has already moved beyond 160,000 barrels per day by November 2017 (it has averaged 167,000 barrels per day for the last six months of 2017)).

Two gas plants were built specifically for the purpose of receiving offshore-produced gas. Domestic gas supply will render Ghana self-sufficient in a few years’ time, which will also allow Ghana to account for hydro-generation shortcomings.

Ghana has been meticulously fine-tuning its regulatory framework, leading to tangible improvements in efficiency and transparency.

Future drilling results might cool down the potentially emerging oil hype, so Ghana’s oil bounty might in fact be overestimated. Drilling results in some areas have been largely disappointing. However, a new major discovery would provide a boost to Ghana’s exploration and production activities. No significant discoveries have been made since 2012 and exploratory drilling activity has been very limited, partly due to the international boundary litigation.

It seems Ghana is well-placed to deliver on its promises. Given the uncertainties prevalent in this industry, Ghana’s government must target the diversification of its economy as a priority. Should they not do so, they might very well go the same route as Nigeria and Angola who have both become victims of the collapse of the oil price.

Ghana’s agriculture sector

Ghana is blessed with vast arable lands, yet spends millions of dollars annually on food imports. In addition, the contribution of agriculture, which is largely touted as the backbone of Ghana’s economic development, has seen a steady decline over the past eight years. From a GDP growth of 7.4% in 2008, the sector declined to as low as 2.4% in 2016. In order to arrest the declining trend and reverse this situation, the new government has introduced its flagship agricultural policy “Planting for Food and Jobs”.

This five-year long policy is geared towards increasing food productivity and ensuring food security for the country, as well as reducing food import bills to the barest minimum. It is also an attempt to modernise agriculture and create jobs for Ghana’s youth.

The policy is built on five major pillars:

1. Supply of improved seeds to farmers at subsidised prices (50% subsidy)

2. Supply of fertilisers to farmers at subsidised prices (50% price cut)

3. Free extension services to farmers

4. Marketing opportunities for produce after harvest

5. E-agriculture (a technological platform to monitor and track activities and progress of farmers through a database system)

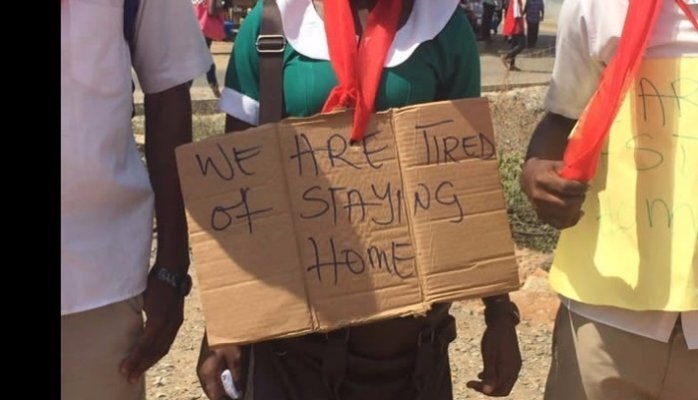

An estimated 200,000 farmers are expected to participate in the pilot phase. This figure will increase in subsequent years. It is expected that hundreds of thousands of direct jobs will be created as many youths will be encouraged to take advantage of the attractive incentives involved in the campaign.

An interesting recent development has been the call for the ban of the export of raw cashew nuts by the Association of Cashew Processors of Ghana (ACPG). The association, which seeks to formalise the operations of cashew processors in the country, believes this would enable them to add value to the nuts, which would bring in more foreign exchange for the country. It called for the introduction of regulations that would support local processors. “Government should create systems and opportunities that would at least ensure first stage processing to be done in the country before they are exported.”

Currently, there are 14 cashew nut processors, a number of kernel roasters and cashew apple processors in Ghana that represent the value-added segment in the cashew value chain. However, only a few of these processing businesses are currently operational.

Ghana’s cocoa industry

One aspect that needs attention in the agriculture sector, and that generates investment opportunities, is the pricing instability in the cocoa sector. Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire contribute about 60% of the world’s production of cocoa; both lost billions due to the fall in cocoa prices on the world market. Only 2% of global revenues generated by the chocolate industry returns to Africa, a very skewed distribution. However, Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire should not just focus on the price of the raw product. They should also attempt to diversify into other areas of the cocoa (chocolate) value chain.

While the president of the African Development Bank (AfDB), Akinwumi Adesina, quite recently pleaded for Africa’s producers of cocoa to produce its own chocolate, this may not be the optimal solution. Chocolate is an expensive product and the majority of Africa’s population cannot afford it. Producing chocolate for the export market is also not an ideal strategy as it is normally produced close to the market, given the expensive nature of its supply chain, which requires cold storage when transported. This would increase the cost of such logistics.

Cocoa expert Victoria Crandall is of the opinion that West Africa can extract more value from its cocoa production by continuing to invest in grinding lines, especially in cocoa butter and powder, which command a higher price than block cocoa liquor. An expansion in cocoa processing capacity, coupled with a control of its cocoa crop so that output stays in tandem with global demand, are critical in helping Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire extract more value from its abundant cocoa production.

Boosting Ghana’s manufacturing sector and industrialisation drive

In August 217, President Akufo-Addo launched the government’s “One-District-One-Factory” project, which aims to create a value-added industrialised economy with the development of at least one factory or enterprise in Ghana’s 216 districts – driven primarily by the private sector. This project will facilitate addressing the challenges of slow economic growth at the district level.

The intention of this industrialisation drive is to equip and empower communities to utilise their local resources in manufacturing products that are in high demand both locally and internationally. According to the president, the route to creating high-paying jobs that will enhance the lives of Ghanaians, is through industrialisation. Raw material producing economies do not produce prosperity for the masses, and his government would change the structure of the Ghanaian economy from a dependence on the production and export of raw materials to a value-added industrial economy.

This project is expected to facilitate the creation of between 7,000 to 15,000 jobs per district and between 1.5 million and 3.2 million jobs in Ghana by the end of 2020. It will also allow Ghana to reap the rewards of industrialisation, increase agricultural and manufacturing output, and reduce the reliance on imports and increase food availability. In addition to these benefits, the project, if successful, will also address rural-urban migration by giving the rural population an incentive to remain in the rural areas. This in turn will reduce the pressure in urban areas on infrastructure such as housing, services, jobs, etc.

As far as implementation is concerned, by early January 2018 it was reported that the “One-District-One-Factory” secretariat was gearing up to commission 69 more factories in the course of the year. The secretariat had forwarded 69 business plans and proposals between 6 October and 21 December 2017 to participating financial institutions to study; 28 of such proposals were submitted to GCB Bank and the remaining 41 to Ghana EXIM Bank. Ten additional projects have also been submitted to the AfDB for infrastructure support.

The proposals thus far cover five broad sectors, namely agro-processing – livestock (10), agro-processing – crop (27), hospitality/fashion (15), manufacturing (other than agro products) (16) and health (1).

GCB Bank Limited has allocated GH¢1.0bn (c. $220m) in support of the “One-District-One-Factory” project. The bank will also offer an array of price concessions for businesses that will operate under the policy initiative. In addition, the Agricultural Development Bank (ADB) Limited has earmarked GH¢200m (c. $45m) to support the programme.

According to the Daily Graphic, the president gave an assurance that 51 districts would have working factories by the end of 2017. While not much has been seen or heard of the 51 factories that were promised by the president by the end of 2017, the Daily Graphic believes that a lot of preparatory work is ongoing to ensure the delivery of the promised factories as soon as practically possible.

In addition, many international organisations and Ghana’s bilateral partners have shown a keen interest in supporting the initiative. One example is the willingness of Chinese companies to utilise the incentives of the “One-District-One-Factory” policy to invest in Ghana. The Chinese company, Sky Team Ningbo, will be setting up sugar-processing and cylinder-manufacturing factories in Kumasi and Sogakope, respectively. This company will provide work for about 1,000 to 2,000 people in the sugar factory, and about 100 people in the cylinder manufacturing factory.

According to the lead project manager of Ekumfi Pineapple Processing Factory, the first factory to be constructed under the “One-District-One-Factory” project, the factory had cultivated 650 acres (263 hectares) of pineapples by mid-March 2018. The Ekumfi Fruit Processing Company factory, when completed, is expected to process pineapples for the local and international market. The project will in total cultivate 3,000 acres (1,214 hectares) of pineapples. About $5m is expected to be invested in the project.

A deputy trade and industry minister, Robert Ahomka-Lindsay, announced in mid-January 2018 that all the factories under the flagship “One-District-One-Factory” programme should be operational within the next two years.

The investment environment in Ghana

According to the recent analysis by FirstBanC Research, the rise in volumes and value of shares traded on Ghana’s stock exchange is not expected to diminish anytime soon, but will continue this year and possibly next year. The research indicated that the market rally in 2017 was largely driven by financially stable and profitable companies. Their expectation is that this trend will continue into 2018 as the fundamentals of listed equities improve on the generally supportive business environment.

The Ghana Stock Exchange (GSE) was adjudged the best performer on the global equity market in January 2018 after recording gains of over 20%. This was based on improving investor sentiment about the prospects of the domestic economy. Robust economic growth, relative stability of the local currency and improving fiscal space were factors that bolstered investor optimism.

The 2018 Ghana Budget identified various investment opportunities. Infrastructure development figures quite prominently (roads, bridges, railways, schools, dams, irrigation facilities, boreholes, housing). An ICT park is included, as is a solar energy plant.

For this conducive business environment, the Ghanaian government deserves the accolades.

Setting the example

Vice President Dr Mahamudu Bawumia has challenged Ghanaians to honour their civic obligations to the state by filing their tax returns in order to mobilise domestic revenue to help meet development aspirations. Mobilising adequate domestic revenue would also help achieve President Akufo-Addo’s vision of a “Ghana Beyond Aid”.

He bemoaned the poor tax paying culture in the country, indicating that though potential employees in the country are estimated at six million individuals, only about 1.5 million persons are registered with the Ghana Revenue Authority and pay their taxes. According to Bawumia, the president had directed all ministers of state, government appointees and public officials to file their tax returns before the deadline. Vice President Bawumia, together with a number of ministers and deputies who were at the launch, subsequently filed their tax returns at the offices of the Ghana Revenue Authority in Accra.

The future

President Akufo-Addo was elected to office on a campaign that touted economic diversification, curbing corruption and enticing foreign investment.

According to tralac in June 2017, Ghana’s economic prospects depends on whether Akufo-Addo’s administration can restore fiscal discipline and regain investor confidence. Fiscal discipline and transparency will be needed to achieve macroeconomic stability, debt management and market credibility. To curb the accumulation of new debt, the government will need to achieve a sufficient primary fiscal surplus. Improving macroeconomic conditions should also reduce financing costs over the medium term.

A difficult external environment may complicate the stabilisation process. Ghana’s medium-term growth prospects are still subject to external risks, including a further deterioration of commodity prices. Recent terms-of-trade shocks have highlighted the country’s macroeconomic vulnerabilities. They have also underscored the urgency of building fiscal buffers and promoting economic diversification to improve the economy’s resilience to further terms-of-trade shocks and help to mitigate the negative impact of an anticipated decline in oil production after 2021. Stronger efforts are needed to unleash the private sector’s potential outside the extractive sector to enhance Ghana’s economic resilience.

Ghana’s heavy reliance on primary commodities, including cocoa, gold and oil – all prone to volatility in international commodity prices – create uncertainty about its actual future paths for growth, inflation, export receipts and domestic revenue.

Razia Khan, chief economist for Africa at Standard Chartered Bank, expects Ghana’s growth story to become more nuanced in 2018. There will be much more focus on whether a robust recovery in the non-oil economy manifests itself.

In this regard, the interest shown in Ghana by global financial services company, Allianz, is a clear example of the growth potential on the non-oil economy. According to the vice president of Ghana, the country’s government is committed to create an enabling environment for businesses to grow and for the creation of employment. According to him, President Akufo-Addo’s administration was undertaking the necessary structural and economic reforms to create a solid base for the accelerated take-off of the economy and at the same time maintain macro-economic stability. He made these statements during a visit to Ghana by the executives of Allianz SE, a global financial services provider.

In Africa, Allianz is currently present in 17 countries. Allianz Ghana, which began operations in the country in 2009, is a 100% wholly owned subsidiary of the Allianz Group. According to Allianz, they are desirous of learning from Ghana in its global expansion drive and outlined plans to further expand its operations.

From what one can see from the above information, it seems that Ghana has achieved considerable success in transforming its economy and positioning itself for further growth. The country’s projected growth of 8.3% by the World Bank is an indication that this institution is of a similar opinion. The same can be said about the investments in the country by, amongst others, the EU.

What is crucially important is the diversification of Ghana’s economy. It cannot afford to remain focused on the extractive industry or the agriculture sector (especially cocoa) for its growth as it remains a price-taker and has very little control or influence. Value addition at source is going to become even more important, as is its economic diversification.

Ghana is clearly making the right statements and have started various initiatives. What remains to be seen is whether they would be able to implement continuously as they proceed into the future.

The author, Johan Burger, is the director of the NTU-SBF Centre for African Studies, a trilateral platform for government, business and academia to promote knowledge and expertise on Africa, established by Nanyang Technological University and the Singapore Business Federation. Johan can be reached at johan.burger@ntu.edu.sg