I waited nonchalantly in the queue. Why all this suffering when it was a formality to get my visa to the U.S. with my British passport?

“Have you got the bank statement?” he asked.

“No, it didn’t say anything about that on the website,” I said.

“Your visa application is refused.”

His voice was terse. He behaved as if I were guilty. There was no sorry. No explanation.

I shook my head in disbelief, trying to explain that I had a business and enough money to cover all my expenses for the 10-day trip to the States, but that I didn’t think of bringing proof. Having a British passport and applying for a self-funded low-residency MFA program, I didn’t think I required the statement.

I also wanted to say that I had an ESTA visa, which meant I could visit the States anytime.

He shook his head, handed me a refusal sheet that covered the embassy legally, and waved his fingers as if I were a fugitive seeking asylum. My face turned red. As I walked out, I knew that I’d messed up. I had been too arrogant.

I had never seen what others went through. I should have done my due diligence better and thoroughly prepared all necessary documents.

As soon as I was back in my office, I went online, booked another appointment and started to gather all the documentation for the next interview. I was in control now. I would get the visa as soon as they saw all the right documents.

Two weeks later, I arrived at 7.30 am, only to find approximately 80 people waiting ahead of me—and all had the same appointment time. We waited outside in a long queue, the sun beating down hard. My head started throbbing, and I thought of bailing to come back another day. Why couldn’t I just send an assistant to handle all this?

I could feel the tension in the crowd, as many Ghanaians were applying to study or visit family, both of which could lead them to a substantially better life than the one they had in Ghana. I watched as parents, friends and relatives supported applicants—training them on what to say and how to act.

I felt sorry for them.

Finally inside a vast, air conditioned waiting room, I watched as applicants answered apprehensively. I looked at their faces after the interviewer broke the news. At one window, there were some raised voices, at another, a young boy left in tears, while a woman waved triumphantly at the last.

Finally, I was called to window eleven, where my interview would take place. This time ‘round the guy smiled as he looked at my application.

My heart started beating faster, and I was surprised at my nervousness.

He asked a few mundane questions, then shook his head and said, “I’m sorry, but when an application is refused the first time, it’s difficult to accept the second time around.” He seemed apologetic. He wanted to be helpful, but he was also new at the embassy.

He summoned his colleague to check on my application. The same person who refused it the first time. He shook his head indignantly. How dare I apply again? he seemed to be saying. I wanted to jump through the window and punch him in the face.

The sweet guy looked at me and shook his head again. “I’m sorry, but I have to refuse it again,” he said.

“But I have all the papers to prove everything you need to know,” I said.

He looked bewildered.

“The last interviewer asked for a bank statement. I have it, and it covers the full tuition and my stay there. At least have a look at it before you say no,” I said.

“I’m sorry, but I can’t. All I can say is that it’s difficult to get a visa from Ghana to the U.S. at the moment.” he said.

For the first time in a long time, I felt helpless. There was nothing I could do. I wouldn’t be going to the U.S. There would be no MFA in writing for now. No sitting in a poetry class, listening to a famous writer read an excerpt. No workshopping my written work.

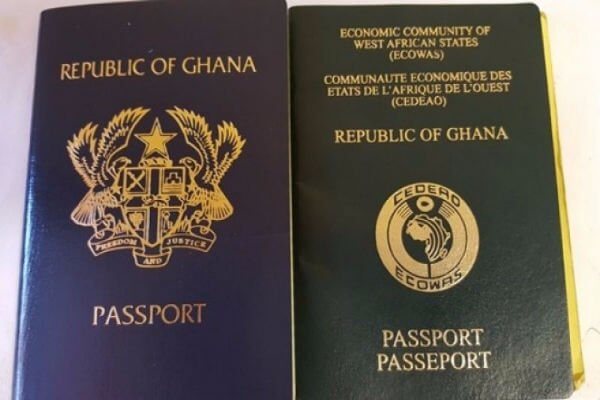

I finally felt the humility that so many people go through when they apply for a visa. I’d never had to go through any of it before, because my British passport got me everywhere, even to the U.S. for a visit—but not as a student on an F-1 visa, which falls under different criteria.

I felt not only confused, but belittled by the whole experience.

I understood that the U.S. had a right to refuse my visa, and that with the rise of terrorism they needed to be extra vigilant. However, the whole process could have been undertaken with more class and more intelligence. To see my dream stolen away because of one person’s idiocy and something as silly and pedantic as this visa procedure was hard to swallow.

I’d lived all my life for one concept: Freedom. Not needing anyone or anything to live my life. To reap the fruits of my actions independent of luck, other people’s judgements, bad days and prejudices. Now, I had to accept that there was nothing I could do to change the outcome.

“There’s nothing I can do,” I said to myself over and over again. The thought calmed me.

The next day, I got a call from the embassy telling me to come in the afternoon and that there would be no queue. “Just quote your surname, and you’ll be taken to the right window,” the caller said.

I was ushered to window seven now, where Mr. Sweet Guy was waiting.

“I couldn’t sleep well. I kept thinking about your application and felt you needed to be heard, at least,” he said.

He reviewed everything, went through his checklist, and smiled at me.

“This is highly unusual. I’m sorry for what happened earlier. I’m reversing the decision and giving you a visa. Collect the passport in a week’s time,” he said.

The staff member who rejected my application the first time around and who wouldn’t even hear me out was standing beside my new best friend, smiling as if to get into the act. I ignored him and looked at the person who called me. I felt a rush of adrenaline flow through me.

“Thank you, sir. I guess that’s why so many from the third world want to go to a first world country like the U.S. Because overall it’s still a fair country.” I said.

I walked out with a sense of relief and humility. At the end of my ordeal, the right thing was done. Life was fair.

I now move on to my next challenge. The MFA learning experience looms on the horizon, and so does my travel to cold, wintry Vermont at the start of the year for the first part of the course.

I’m thankful that one man was determined to make things right. He had the courage to do so, even when it was easier not to. I know as I write this that many others have not been as lucky as I was in their treatment by embassies all over the world.

I think life often plays a bigger game than we realize. I’m coming to understand that we must trust life and let it lead us, rather than becoming an obstacle to it.

Humility is a powerful way to park our egos and allow life to do just that.

Credit: Elephant Journal