The slump in commodity prices and the associated economic uncertainties are forcing African countries to explore new development strategies that are more durable. One obvious shift is investing in human resources by building scientific and technological capacities.

This would be a dramatic departure from the conventional focus on the continent’s natural resources. The transition requires African policy-makers to focus more on how their own societies can shape their scientific and technological trajectories.

African societies – with their myriad economic and social challenges – offer the richest test-bed for scientific and technological research. They also offer unprecedented opportunities for applying the world’s abundant scientific knowledge and engineering expertise to solve societal problems.

Scientific research for the greater good

Conventional wisdom informs African policy-makers that their economies are likely to grow if they invest significantly in basic research and development (R&D). The case is often made for devoting a minimum of 1% of a country’s GDP to R&D. The assumption is that investing in research would result in new technologies, which would then be deployed in the economy to boost development and improve human well-being.

There is justification for investing in R&D, but not because of the linear view of such investments. This approach has been sold to African countries over the decades and continues to be promoted uncritically. This view assumes a one-way flow of events: from basic to applied R&D, and to societal impacts.

The view also treats science as if it was something that happens outside society. This perception is not unfounded. Many in the scientific community would prefer to receive financial support for their research without the related expectation of addressing social challenges. It is not uncommon for the scientific community to argue for increases in research funding, while at the same time seeking independence from close government scrutiny.

As outlined by the African Union’s 10-year Science, Technology and Innovation Strategy for Africa 2024 (STISA-2024), the real reason to invest in R&D is to respond to challenges in key sectors such as agriculture, health, ecological management and the built environment. This approach does not negate the importance of scientific research – it simply seeks to connect scientific and technological endeavours to broader societal needs.

Much of Africa’s scientific advancement will come from technologists and engineers whose obstacles might yield new scientific insights. The second law of thermodynamics, for example, stemmed from efforts to improve the steam engine. The technology was first developed to address a practical challenge of helping to pump water from flooded mines. In this case, science followed engineering. The point here is not to argue against basic research, but to underscore two important points. First, that scientific enterprise is likely to receive greater support if it is directly connected to societal needs. Second, a creative and open approach to scientific research needs to acknowledge the two-way traffic for scientific discoveries.

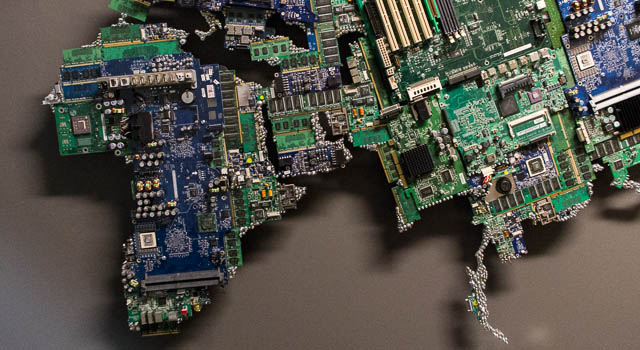

Science can therefore be advanced as part of the ongoing investments in infrastructure projects and expansion of entrepreneurial activities across the continent. Using a similar approach, African countries could start to think of their natural resources not solely as export commodities but reservoirs for geological knowledge, as well as a basis for advancing material science and technology.

An African tech revolution

Efforts to address Africa’s problems in diverse fields might yield new scientific discoveries that are directly linked to the continent’s challenges. In this respect, science would serve society just as society serves science. The two co-evolve and shape each other in complex and dynamic ways over time.

Indeed, advances in the application of mobile technology in Africa are starting to shape fundamental research as young people discover the importance of mathematics and electronic engineering in the development of new products such as apps and digital services. Similarly, a few African research institutions are starting to harness the power of nanotechnology to explore new properties of natural resources that can be leveraged to develop new products.

In the same vein, Africa can leapfrog decades of prior technologies by starting to harness for civilian use the power of technologies such as solar photovoltaics, 3D printing, drones, robots, satellites and synthetic biology, especially gene editing.

African countries are already at the forefront of harnessing these technologies. For example, Rwanda has set itself the ambitious goal of building the first drone airport in the world. An increasing number of African countries are leveraging drone technology to address a variety of resource mapping, delivery and agricultural services. It is through such efforts that salient basic research challenges are likely to emerge.

Pushing the frontiers of agricultural research in response to challenges such as climate change and drought is likely to yield new scientific breakthroughs. Such research results will the lead to further advancement of agricultural research and economic development. The relationship between the two is not linear but iterative.

A more holistic approach to scientific innovation

One of the key implications of acknowledging the interactive approach is the need to abandon the false dichotomy between STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) subjects on the one hand, and the social sciences and humanities on the other. Instead, the focus should be on promoting creativity though the integration of the diverse disciplines. Inventors need legal expertise just as much as medical researchers need anthropological knowledge. The demarcation is a relic that only perpetuates the under-utilisation of knowledge for development. It also creates opportunities for unnecessary feuding over limited financial resources.

The co-evolution between science and society challenges not our world view about the place of scientists in society, but the very definition of what we consider to be science. It also calls into question the dominant design of the research landscape among most African countries.

There is a popular view that separates science from other technical fields, especially engineering. In fact, much of the work of engineers is credited to scientists, especially by the press. Scientists take the credit for new technology products and engineers usually shoulder the blame when technologies fail.

Accepting the view that science and society co-evolve requires the recognition of engineering and other disciplines as being integral to the research enterprise. Forums that bring scientists together should also endeavour to accommodate technologists, engineers and associated experts from the social sciences and humanities.

This has implications on the way that universities are structured. It calls for greater emphasis on trans-disciplinary collaboration. Such an approach is not just about the token inclusion of experts from other fields, but about genuine efforts to bring the diverse disciplines together to help find solutions to social problems.

A new generation of universities

Equally important is the need to address the common separation between research, teaching, extension and commercialisation of new products. In many African countries such separation is buttressed by law. Research institutes undertake research but they do not teach. Conversely, university lecturers concentrate on teaching with limited support, incentives or time for research.

There are two debilitating consequences of this separation. First, by not having students, research institutes lack the basic human capacity to move their results from laboratories to the marketplace. In more dynamic innovation ecosystems, this function is performed by university students or recent graduates. Universities that do not undertake much research end up passing on outdated knowledge to successive generations of students. Today’s rapid rate of scientific advancement renders such knowledge obsolete in the early stages of the professional lives of lecturers.

An obvious outcome of such trends is the decline in the quality teaching and the irrelevance of the knowledge that students acquire. These impacts generally undermine the credibility of research institutes and universities. They also make it harder to argue for increasing their financial support.

One way to bridge these gaps is to gradually create a new generation of universities that combine research, teaching, extension and commercialisation of new products and services. Such “innovation universities” should reflect the view that science and society co-evolve.

Indeed, some countries reflect this confluence in the structure of their ministries. Japan, for example, has one ministry dealing with education, culture, sports, science and technology. In many African countries, science is viewed as the opposite of culture. Most African governments lump culture with arts, tourism and handicrafts. Only Comoros has research and culture under one ministry. The point here is not to copy the Japanese model, but to highlight the fact that most African countries consider science to be separate from culture. The tendency is to define culture in static terms despite considerable evidence of creativity in handicrafts, making them centres of innovation.

Improving the capacity of existing institutions to foster research requires building capacity in innovation management. It is for this reason that the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) has launched the Technology, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship in Africa (TIE-Africa) Executive Programme with a US$1m gift from the Schooner Foundation to assist African countries to build their innovation management capacity.

The time has come for African countries to view their social and economic challenges as opportunities for scientific advancement. It is also time to bring science and other fields, such as engineering, the social sciences and humanities, together to help address societal challenges. Only through such collaboration can we hope to advance both science and society as an integral whole.

Author: Calestous Juma is a professor of the Practice of International Development at Harvard Kennedy School, Harvard University. This article was originally published by the World Economic Forum in collaboration with Africa Policy Review.