Across Africa we see a common trend. The continent is powering up. In our new series on power privatisation in Africa, Africa Oil & Power examines five case studies.

Ghana is experiencing its biggest energy crisis in more than a decade. Amid a power generation shortage of around 500 MW, the country is losing GDP growth of between 2% and 5% as industries are unable to operate at optimal power efficiency. In 2014, following the signing of a candidacy agreement with US agency Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), the Ghanaian government agreed to the liberalisation of its power sector in return for US$500m in investment to turn around the crisis.

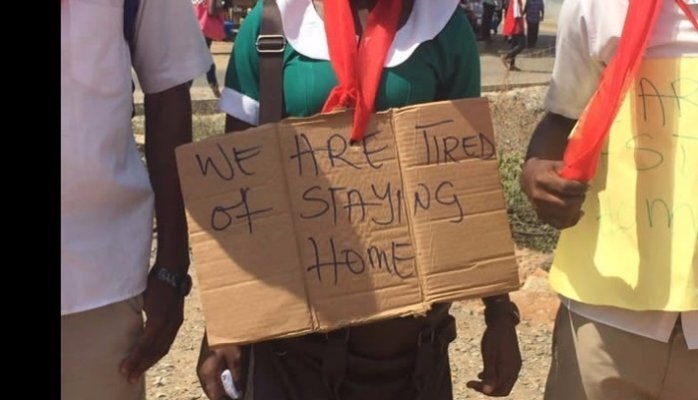

Despite demonstrations on the streets protesting the 12-24 hour blackouts in Ghana’s biggest cities, the idea of privatising the national electricity distributor Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG) has not met wide support.

Regulation

The energy market has been relatively liberalised for years, with private operators today contributing around 326 MW of the country’s 2,125 MW output. According to the government, as many as 30 companies have licences to produce power, and some of them have power purchase agreements. But only two of them – Sunon Asogli and CENIT Energy – produce any power so far. Be it because of low tariffs or any other type of barrier, IPPs are not helping Ghana pull out of this crisis. Discussions to privatise ECG (which covers distribution for the south of the country) are taking place.

Implementation

The government of Ghana is hoping that two new projects, a 350 MW plant in Kpone headed by Cenpower and a 360 MW plant in Inchaban headed by Jacobsen, will help curtail power shortages as demand continues to rise. The country faces further infrastructural difficulties as ECG’s decaying infrastructure and power theft mean that 21% of the country’s generated power is lost. The options available to ECG include a partial privatisation, a management contract for 25 to 30 years with a private company or a leasing structure. A poor experience with a similar management contract with the Ghanaian Water Company has made the public wary of such deals. In any case, international and local investors have already shown interest in investing in ECG.

Financing

In 2014, the Ghanaian government signed a deal with the MCC for a development grant worth $500m. The conditions to receive the grant included the facilitation of the liberalisation of ECG. The company’s inability to answer the country’s power needs, as well as its growing debt, is seen as a result of mismanagement that could be curtailed by a switch to the private sector. This facilitation, however, also includes the state paying off its $375m debts to ECG at the end of 2014.

Conclusion

While a turn around for the Ghanaian energy sector is urgent, it is questionable whether ECG’s difficult situation is caused by its parastatal management style or because its biggest client, namely the government, does not pay its bills. What is clear is that the government will face an uphill battle if it decides to go ahead with the privatisation of the ECG, particularly in view of President John Mahama’s pledge to fix the energy crisis before 2017. Which is another way to say, before the elections in December 2016.

Source: howwemadeitinafrica.com